Death Hoax, It’s A Serious Problem That Isn’t Going Away

Is He Dead? Of Course He Is! I Saw It on Facebook, So It Must Be True

A death hoax is a deliberate or confused report of someone’s death that turns out to be incorrect. It’s not a new problem but it is a growing problem and it’s getting worse.

From Wikipedia;

In recent years fake death hoaxes about celebrities have been most widely perpetuated via the Internet. However they are not a new phenomenon; in 1945 following the death of Franklin Roosevelt there were hoax reports of the deaths of Charlie Chaplin and Frank Sinatra, among other celebrities of the time. Possibly the most famous hoax of this type was the “Paul (McCartney) is dead” rumour of the late 1960s.

Hoaxes about the death of a celebrity increase in frequency when genuine celebrity deaths occur. With the 2009 death of Michael Jackson, which closely coincided with the deaths of Ed McMahon, Farrah Fawcett, and Billy Mays, hoax reports emerged concerning the deaths of a number of celebrities.

Last night I read the following article on HuffingtonPost.com and found it to be insightful on how easily a death hoax can be started and how little thought process goes into the immediate repercussions that unfold. With social media as the primary driver, a death hoax can be put into motion and immediately effect thousands of lives. As this type of prank continues to grow, how will it effect our reaction to death announcements?

From HuffingtonPost.com

Is He Dead? Of Course He Is! I Saw It on Facebook, So It Must Be True

By: Benjamin Solomon Editor-in-chief, Next Magazine

Last week I did something terrible. As Sandy ravaged the city of New York, I got a little too drunk after dinner. Bored, I decided that it would be fun to play a prank on a good friend of mine: I would pretend that he had mysteriously died. After all, it would be so easy. I had Facebook.

With a simple, ambiguous post on his page, I lead everyone to believe the worst. I wrote, “You will be missed. A bright light has gone out in the world.” That was it. Within 15 minutes I had received almost 20 text messages from close friends horrified by the news. Quickly realizing the error of my ways, I assured them that all was OK and apologized to them for my insensitivity during the storm. But a second wave of strangers immediately began to respond on Facebook, even posting their own thoughts and memories. What had I started? I had just meant to joke around with my friend, but it had become a much more public problem.

Deep down I’d known that this was going to happen. After all, in the last few months I had learned about the deaths of several acquaintances via Facebook. Similarly ambiguous posts had begun to fill my news feed with sweet, non-specific remembrances of a person I barley knew. “Did this person really die?” I would think. “How terrible would it be for death rumors to spread and that person still be alive?”

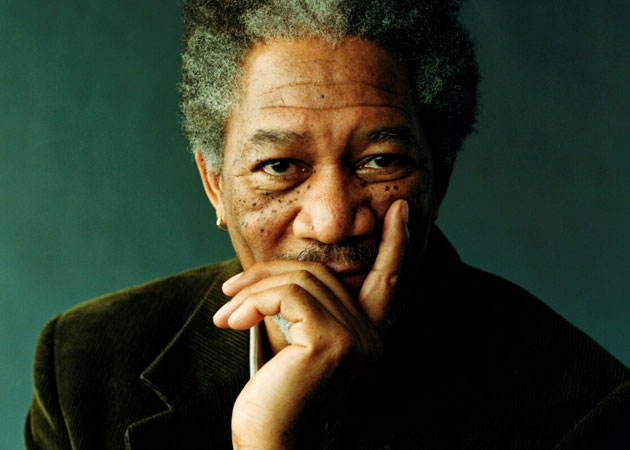

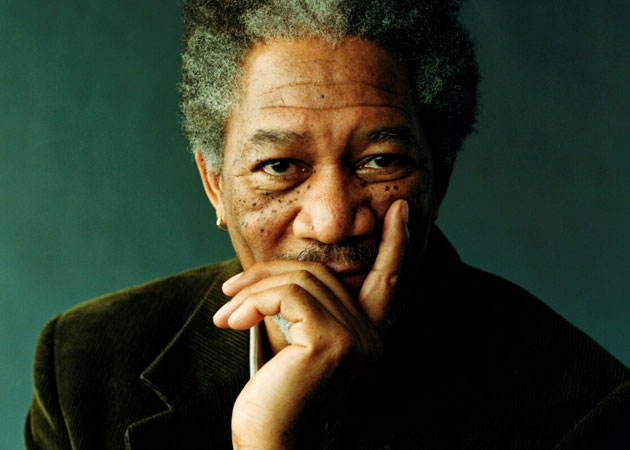

Sadly, it happens all the time. In fact it has a name: the death hoax. And while a false reporting of a person’s death is nothing new, the age of Facebook has made the spreading of such rumors so much easier. Tony Danza, Bill Cosby, Jerry Springer and Justin Bieber have all been rumored to have passed thanks to a simple tweet sweeping through the Interwebs. There is even a website that helps people make their death hoaxes look more credible, called Fake a Wish. And this September Morgan Freeman’s representative had to make an official statement that his client was, in fact, not dead, as Facebook had claimed. “He’s still alive and well,” the rep said, “Stop believing what you see on the Internet.”

Aside from being a bizarre social media fad, death hoaxes, as Freeman’s rep pointed out, are evidence of a larger, much scarier trend on the Internet: believing that everything on the Internet is true. As traditional media — with their fact checkers and thorough researchers — succumb to the who-can-break-the-story-first news cycle of the blogosphere, more and more misinformation pervades our lives. Do we dare to question the validity of a story and risk not being one of the first people to report it? When Antoine Ashley, known as celebrity drag queen Sahara Davenport, was reported to have died, almost every outlet reporting on his passing cited Twitter posts days before any police report or announcement from family members. Even LOGO, the channel that propelled Ashley to stardom on RuPaul’s Drag Race, referenced the tweets in their original Facebook post announcing his passing. Did they know for sure, or where they too afraid of looking insensitive by waiting to confirm the truth?

And this isn’t just limited to death rumors. In July a blog post about Rick Santorum using gay social networking app Grindr swept across Facebook, its readers failing to realize that the piece came from a satirical website — possibly because they failed to read the article before reposting and retweeting it. Sandy, too, had plenty of Twitter users crying wolf.

There is no doubt that the aggregation of information — and specifically news — has empowered humanity in a way like never before. This is evidenced in everything from Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign to the Arab Spring. But as we increasingly turn to our friends and followers for news, it is important that we do so prudently.

When it comes to death, Facebook has become a very odd tool for mourning: a living memorial and a place to share memories. In fact Facebook policy dictates that your page should remain as a place for friends and family to pay their respects after you die. It’s a sweet thought indeed. But when it comes to news, a tool like Facebook is all about being first, to show your friends that you know what is going on — like announcing the death of a person you only sort of, kind of knew.

So what happened with my terrible, tasteless prank? Before things got to out of hand, I alerted my friend to the thoughtless deed. (For the record, he did find it funny, “though in a dark Todd Solondz kind of way”). And, thankfully, he was able to intervene before his family could see the false news. He posted that all was fine and, despite the rumors, he was very much alive. That post being on Facebook, I assume they all believed him.

Follow Benjamin Solomon on Twitter: www.twitter.com/benjaminsolomon