How Deathcare HASN’T Changed Since the 1880s

How many times have you heard that deathcare is antiquated, behind the times, or one of the slowest industries to evolve? Most of us would disagree, or at least push back a little. However, if you look back at the newspapers of the late 1800s, you might be surprised how much has actually not changed in the last 130 or so years. As a matter of fact, the undertakers of the 1880s and 1890s were a lot like you. Take a look:

They gathered for deathcare conventions

Like those who attend the annual NFDA, CANA, and ICCFA get-togethers, the undertakers of the 1880s knew how to party! The 1885 New York State Undertakers’ Association (aka “Knights of the Shroud”) convention was an “assemblage of grave people” that attracted more than 2,000 professionals, including members of the Brooklyn branch. Interestingly, that borough’s constitution didn’t allow members to deal with manufacturers of “caskets and coffins or jobbing house of undertakers’ supplies” if those entities did business with non-members. It also didn’t allow them to pay for advertising, and “under no circumstances must prices be advertised.” Additionally, the Brooklyn association kept a “black book” with names and addresses of families who didn’t pay for their loved ones’ services; those families would be refused services for the second funeral and would have to be “looked after by a scab undertaker.”

They didn’t always get paid

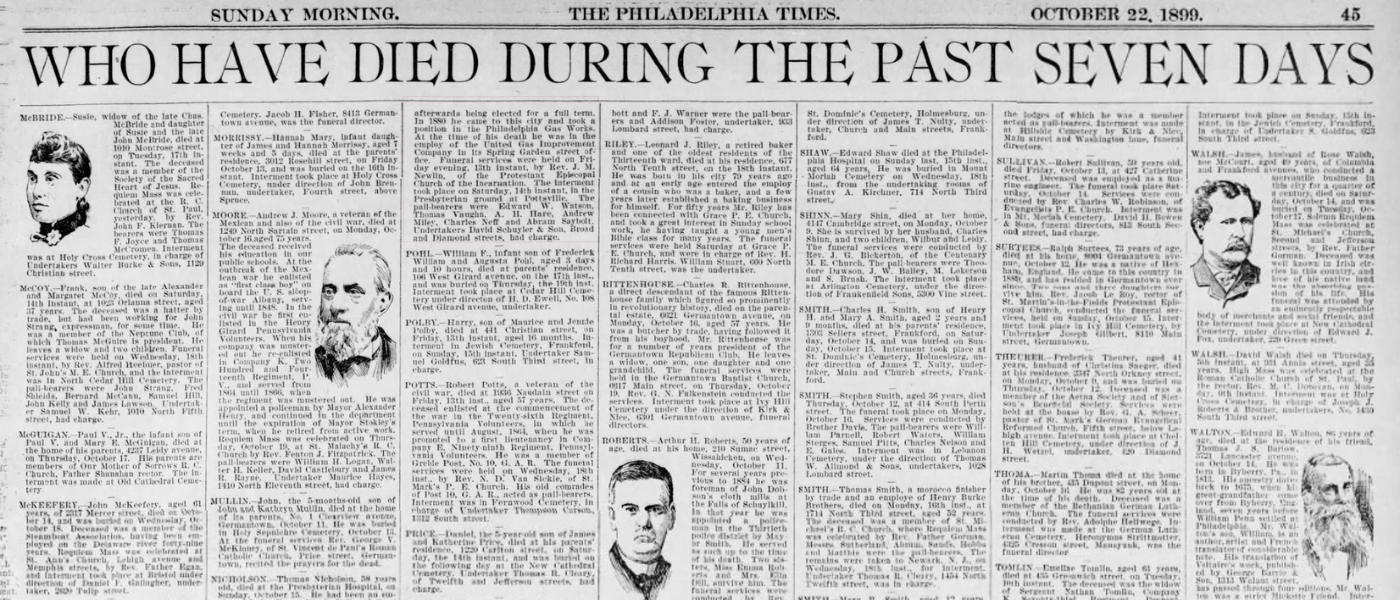

Wouldn’t it be great if everyone paid their full bill up front? Sadly, that doesn’t always happen. It was the same in 1898, when undertakers reported that “no less than one-third of what is due them” was never paid. Then, as now, an undertaker “cannot like an ordinary tradesman demand the pay when the goods are delivered; he must take charge of a funeral without any guarantee for payment for his work.” Sadly, of the over 400 undertakers in Philadelphia in 1898, all but “about a half dozen” had thousands in “dead bills” on their books — and they were mostly from the middle class folks. The paper explained that “the very poor man will seldom contract a bill he is unable to pay” while the middle-class family would often “want the best of everything” to “make the proper show before the neighbors, let it cost what it may.” Some undertakers reported total unpaid debt of $30,000 to $40,000 — at a time when the average funeral cost $65 to $130.

They were always getting requests for price lists

The writer of this 1884 column about the Cincinnati undertakers’ prices not only complained about how hard it was to get a price list; the person also “exposed” the mark-ups. For example, the “actual cost” of the $100 casket “with rough box and including trimming, lining and ornamentation complete” was only $38, while it “actually cost twenty-five cents to furnish each pall-bearer with gloves and crape.”

The article goes on to detail the profits made on the “finest” casket available — the “Occidental” — which might have been the Promethean of the 1880s, as it was reserved for the “higher grade of public men.”

Their work was shrouded in mystery

Reporters, writers, and now TikTokers and YouTubers love to pull back the proverbial curtain on the mysterious world of deathcare, and regular folks still yearn to learn the secrets of the funeral home. It was the same way back in 1880, when a Chicago reporter called on a “number of prominent Chicago undertakers, with a view to gleaning any melancholy items of interest which might be above ground.” His findings? The undertaker, a “necessarily sympathetic man,” who is “always gravely sorting over a bundle of burial permits,” caskets “grouped all around the store,” and “funeral drummers” (sales people) turning up at the funeral home “with their novelties every three months.”

They enjoyed their trade publications

While there was no American Funeral Director Magazine or Connecting Directors back in 1880, they did have The Casket. Within the pages of these deathcare publications was “a very good column headed ‘Temperate Undertakers’ which shows that drinking men are more likely to contract contagious diseases than temperance men.” Another article was titled “Funeral Thoughts by Brother Pensaroso,” and one magazine included a “romance called ‘The Grave-Digger’s Daughter.”

They put the “fun” in funerals

Hooray for the Italian undertaker, who, even back in 1898, knew that funerals could be celebratory and positive experiences. His shop was “the headquarters, in fact, for sociability” where “sometimes the ghost of a laugh struggles out when the warmth from the fire penetrates sufficiently and somebody says something cheerful.” Even the “$8 or $10 coffin under the flaring candles is in no way a hindrance to the exchange of everyday comments and chat.”

On the other hand, some areas of deathcare actually HAVE made some progress:

Thank goodness this “prophecy” that “the day will never come when a funeral will be conducted by a woman” was pure crap. You go, girls!