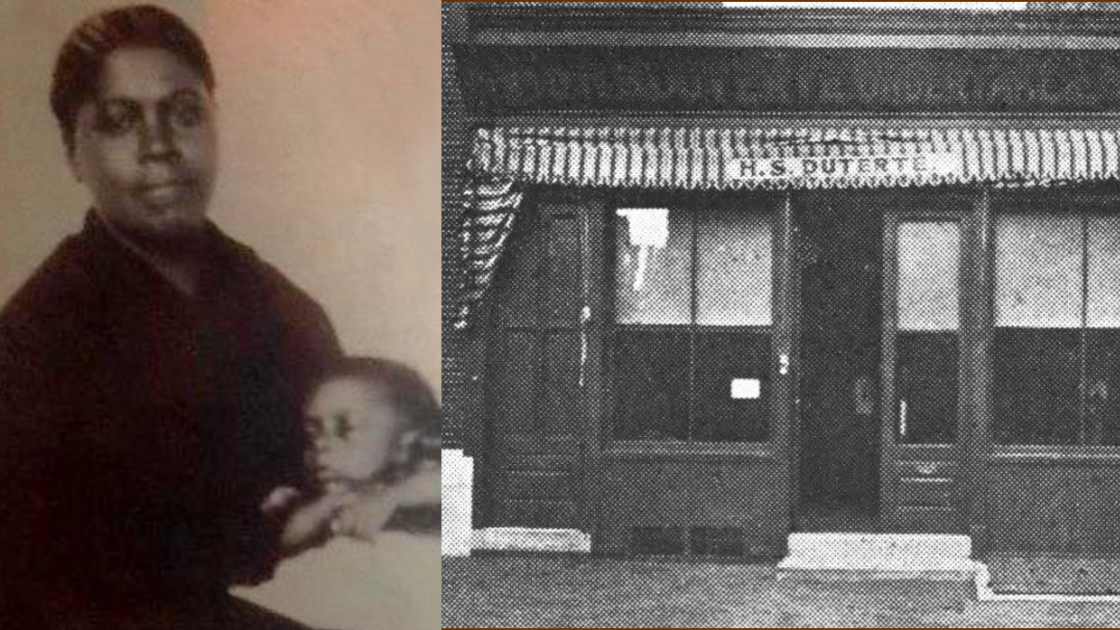

Henrietta Smith Bowers Duterte Paved The Way for All Women

When Henrietta Duterte lost her husband Francis, a coffin builder, undertaker, and business owner, to consumption in 1858, she inadvertently became the country’s first African American woman mortician.

A successful one, too, by any reckoning – having learned the business from the husband, she maintained a business model that recognized the poor and rich on equal footing and provided the black community with a service recognizing the dignity and conferring respect to individuals who were so often denied the same in life.

At a time when racial lines divided the population even after death, Henrietta swerved her entire community without regard to race and built a reputation of excellence, prompt professionalism, and sympathetic equality to all families she served.

Hotbed of Change

Her hometown of Philadelphia in the mid 1800’s was one of the first American cities to abolish slavery with the Gradual Abolition Act of 1780. As a result, Philadelphia had become a hub of economy and professionalism for the black community, and a thriving center for African American business and culture.

The Gradual Abolition Act didn’t institute instant freedom — it dictated that children born into slavery after that date would become free upon their 28th birthday. Slavery itself still remained legal until 1847, and racially-motivated mob violence was not an infrequent occurrence around the nation, but in Philadelphia in particular. As the city closest to the states of the south which still held slaves, it became a destination of the formerly enslaved, as well as those seeking to escape slavery.

Active Stop Along The Underground Railroad

Into this social context, Henrietta set her business to work on behalf of fleeing slaves. She hid people in coffins and passed them off as members of funeral processions, providing safe passage through Philadelphia at considerable risk to not only her business, but to herself: the legal penalties for supporting runaway slaves were stiff and entailed jail sentences, thousand-dollar fines, and potential civil suits from slave-owners.

Madame Philanthropist …

In addition to her rather historic role helping to set captives free, Henrietta’s successful business supplied resources she was able to direct into community support : she financially supported a church her family had been associated with for years, the St. Thomas African Episcopal Church, by paying part of the pastor’s salary. She funded the Philadelphia Home for Aged and Infirmed Colored Persons. And in the wake of the Civil War, she was instrumental in organizing the Freedman’s Aid Society in Tennessee, which assisted formerly enslaved people. Busy lady…

… And Exemplar

And now, America is on another cusp of more social upheaval, but at least we’re not at war with ourselves… not yet, anyway. Nowadays when it feels like everything’s just circling the drain, it’s good to be able to look backward to a time when our society had things so much worse in so many ways, and see that in spite of all that mess, America managed to set forth such a luminary as Henrietta Duterte.

Think about this woman: a widow, she overcame the personal loss of a spouse. The dominant culture largely detested her for her lineage and gender both. Women, in fact, could barely own property at all, and black women almost never held business ownership.

Yet Henrietta Duterte not only kept her husband’s professional legacy alive by herself, she built upon it until she’d established it as her own. She maintained a solvent, robust business, performing her duties admirably, without prejudice, comforting any in pain with equal care.

And she still managed to stand against unfathomable opposition to help slaves go free, work the Underground Railroad, support the faith and welfare of others by keeping a church alive, and benefit a greater cause and her community with her own good fortune.

Thank you, Henrietta, for your example of honor and service. We can surely learn from you now.