What Constitutes a Pandemic?

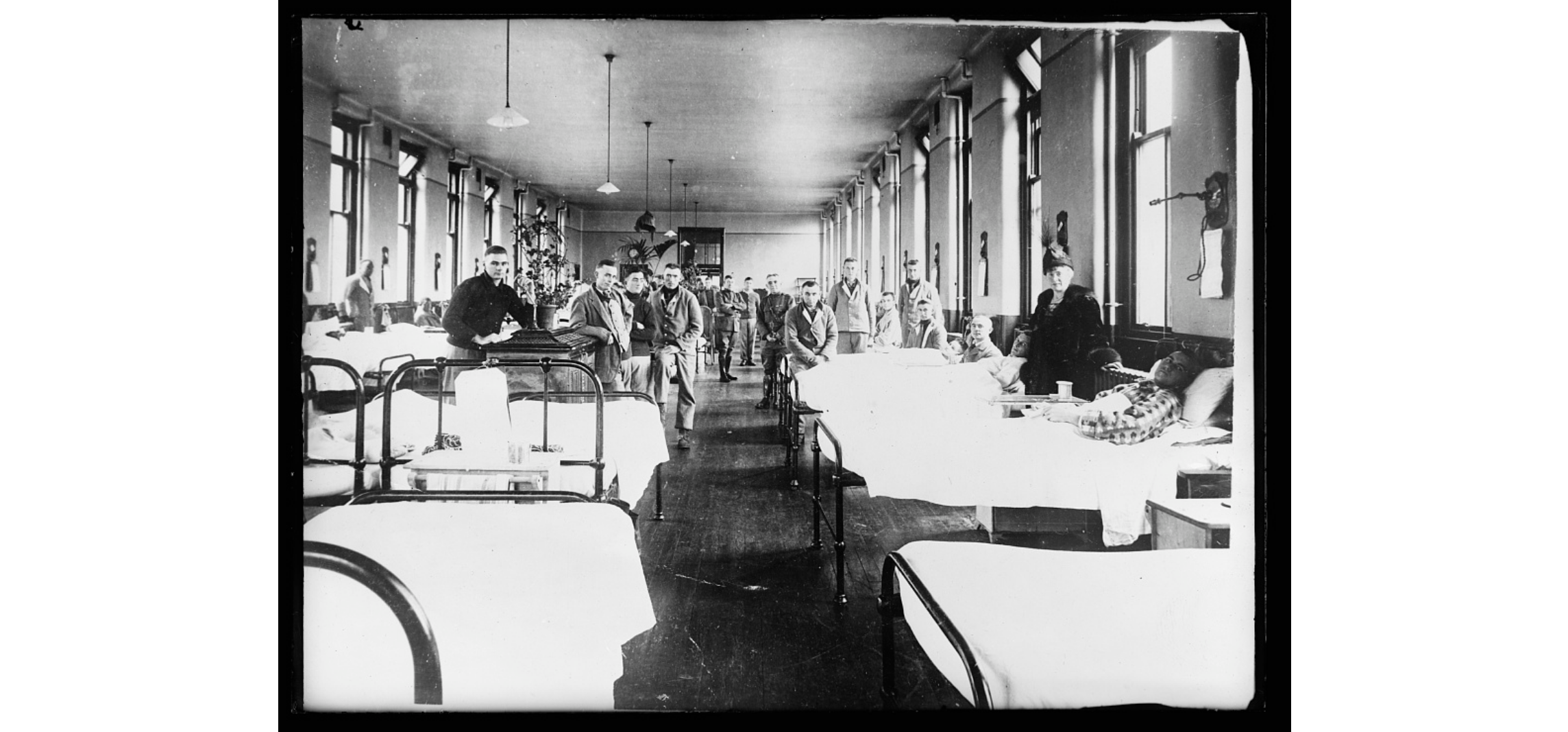

1918, 1957, 1968, 2009: In these years, new diseases emerged. They spread, leapt across oceans and international borders, struck thousands – even hundreds of thousands – dead, then disappeared.

They were named in the standard manner for the places they were first discovered: Spanish flu (1918); Asian flu (1957); Hong Kong flu (1968), and Mexican flu (or swine flu; 2009). Of some of the largest pandemics of the last century, all were influenza pandemics.

Each struck the US with various degrees of fatality: Spanish flu’s estimated 500 million infected had a death toll estimated at 50 million; 675,000 in the US alone. Asian flu estimates of dead worldwide come in at 1.1 million, with 116,000 of those victims in the US. The Hong Kong flu of ’68 had 1-4M dead, unknown quantity infected; about 100,000 of those victims were American. Mexican (swine) flu resulted in 284,000 deaths.

When in the Course of Human Events…

Throughout history, pandemics have shaped and directed human affairs, typically with great impact (consider cholera, or the plague). But pandemics are generally characterized by their limited periods of occurrence. It’s a feature of a pandemic that one comes about quickly, and ends just as suddenly.

Today, however, we know of numerous infectious diseases transmitted between humans that persist globally, recurring at high levels of incidence. The 1957 and 1968 outbreaks, for example, were of related strains of the same virus.

That’s just messed up.

Are Pandemics Getting More frequent?

Not really… but that’s not the good news it may sound like at first. Rather, it’s just always been this way.

COVID-19 has already won the competition for the worst thing to happen, in pretty much every single metric of figuring we’ve got, for this century. But the disturbing reality is that extreme though it may be, monumental occurences like COVID are not rare.

This study examines outbreaks by history to try to determine recurrence patterns and probabilities.

The takeaways are these: that in any given year, there’s about a 2% chance that we could stumble into another pandemic of equal degrees of disaster as the one we’re currently navigating.

Unbelievable and unacceptable, the unfortunate indications are that big, virulent, sweeping arcs of disease kind of hang in the air over our heads like scythes or guillotine blades, not off in fantasy-mists somewhere, back in distant history, or way out in some distant future we won’t even survive to have to experience.

And that probability increases daily.

Thanks for Nothing

The point, of course, was to emphasize the need to adjust our perceptions of what risks look like… both for pandemics and expectations for preparedness.

If large-scale pandemics like COVID-19 and the 1918 Spanish flu are downright likely, then we need revised priorities, and promptly: We need proper recognition of the severity and prevalence of COVID-sized disasters that fit into our every day realities. We could also use some guidance on how both to manage both our efforts, and how to control and prevent them such deadly disruptions.