10 Ways Sextons and Senators Have Historically Defended Corpses and Their Rights

Wouldn’t it be nice if “final disposition” was always, well, “final?” Unfortunately, ensuring that corpses actually end up — and stay, intact or otherwise — where they are intended to rest for eternity is still a problem.

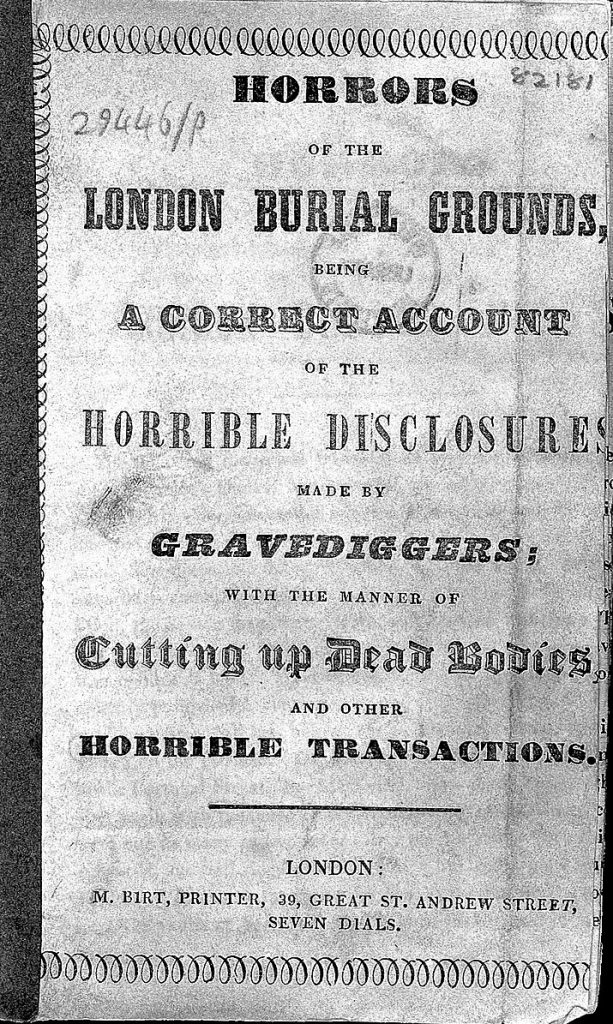

From the 14th through the 19th centuries, we worried about body snatchers. These nefarious folks would dig up the dead and sell them to medical schools to further the study of anatomy. Sometimes, even the medical students themselves were found guilty of procuring their own lab specimens from a nearby graveyard.

In the late 1800s, as the practice of embalming became more popular and allowed medical schools to keep bodies on the dissection table longer, body snatching seemed to meet its demise.

Today, though, we’re dealing with another nefarious folk: body brokers. In a world where people now freely elect to donate their bodies to further scientific study, body brokers fraudulently obtain these corpses and sell them to the highest bidder for the same purpose.

Throughout history everyone from cemetery sextons to loved ones to legislators have sought to defend the rights of corpses to be properly or permanently disposed. Here are just a few ways we’ve battled body snatchers and how, today, we’re fighting to rid ourselves of body brokers.

Coffin Torpedoes

As the end of the Civil War signaled a renewed interest in body snatching, an Ohio man invented a device to teach would-be thieves a lesson. In 1878, Philip K. Clover received a patent for the Coffin Torpedo, a device that would “fire several lead balls into the thief” as he lifted the lid of a coffin during the “unauthorized resurrection of dead bodies.” Another Ohioan, Thomas N. Howell, improved upon Clover’s design, patenting a shell that would be buried above and wired to a coffin. Like a landmine, it would detonate when thieves ran into the wire.

Anatomy Act of 1832

Astonishingly, prior to the early 1830s, no laws prevented the taking of corpses from graves in Britain. According to Britannica, corpses “had no legal standing” and were “not owned by anyone.” Dissection of corpses, though, and theft from graves of items other than the body itself, were against the law. The Anatomy Act of 1832 changed that, deeming body snatching illegal and making more bodies available to medical schools through the release of unclaimed corpses of the poor and ill or by family permission.

Grave Guns

As an above-ground alternative to the coffin torpedo, some cemeteries used grave guns to injure would-be body snatchers. According to an article in Slate Magazine, cemetery keepers would mount a gun at the foot of the grave. The mount allowed the gun to spin freely and fire when someone triggered one of several attached tripwires. “Graverobbers evolved to meet this challenge,” the Slate author writes, by sending women and children to the sites during the day to report on the locations of the guns. Savvy cemeterians, though, would wait until dark to strategically relocate the guns, “thereby preserving the element of surprise.” Sometimes called a “spring gun,” the mechanism was ultimately outlawed in 1827 after inadvertently injuring various innocent cemetery visitors.

State Laws Against Graverobbing and Dissection

According to a 2016 paper by Raphael Hulkower of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, “to this day the only federal law pertaining to cadaver supply was passed in 1790 and gave federal judges the right to add dissection to the sentence of death for murder.” Hulkower continues, “By the end of the 18th century, U.S. state governments began to realize that a dramatic legal change would be necessary to effectively end the practice of grave-robbing. Until medical schools had a good alternative source of cadavers, there would always be a market for illegally obtained bodies.”

“Massachusetts was the first state to enact laws, in 1830 and 1833, allowing unclaimed bodies to be used for dissection. Over the course of the next decades, many other states followed suit, legislating that unclaimed bodies of people who died in hospitals, asylums, and prisons would be allocated to that state’s medical schools for the purpose of anatomical dissection. Due to these laws, the price of illegally obtained corpses declined, making grave-robbing neither profitable nor practical.”

Mortsafes

A contemporary of the torpedo coffin and the grave gun, the mortsafe was an iron grate system intended to protect a grave from being dug up by body snatchers. Unlike other barriers like large stones cemented into place, mortsafes weren’t permanent fixtures. In fact, families formed mortsafe societies, where they would collectively purchase these grates or cages. When a body had decomposed enough to be unattractive to body snatcher, another society member would install the mortsafe on a new grave.

Uniform Anatomical Gift Act of 1968

The Uniform Anatomical Gift Act (UAGA) is a federal law, first declared in 1968. This Act created the power to donate organs, eyes and tissue for transplant purposes throughout the United States. Legislators revised the law in 1987 and 2006 to reflect changes in the practice of organ donation. Among other provisions, the UAGA made the trafficking of organs for profit illegal.

Watchtowers

During the height of the graverobbing epidemic in the early 1800s, some cemeteries would erect watchtowers and pay someone to watch for body snatchers. Many of these watch towers still stand today, especially in burial grounds in the United Kingdom.

Iron Coffins

Cast iron or iron coffins were some of the earliest metal burial containers in the United States. Manhattan stove designer Almond Fisk patented the first airtight iron coffin to facilitate the transportation of his brother’s body from Mississippi to New York in 1844. However, the article above, which appeared in the Charleston (South Carolina) Daily Courier in July 1820, shows that iron coffins were already being used in London to prevent the body from being removed by “resurrection men,” or body snatchers.

Dead Houses

Alternatively called mort houses, charnel houses, or receiving tombs, dead houses were structures built to store bodies at cemeteries when the ground was too frozen to dig a grave. Since body snatchers preferred recently-deceased corpses, sextons would securely lock and heavily guard these dead houses. Dead houses were quite popular in Canada in the 19th century before modern machinery facilitated digging into frozen ground. In fact, dozens of dead houses still exist today across the Canadian landscape.

Consensual Donation and Research Integrity Act of 2021

In June 2021, the National Funeral Directors Association (NFDA) issued a release in support of H.R. 4062, the Consensual Donation and Research Integrity Act of 2021 (CDRI Act,). Reps. Bobby Rush (D-IL) and Gus Bilirakis (R-FL) introduced the act to the House of Representatives. Its intent is to “transform the landscape by providing the Secretary of Health and Human Services with oversight of entities that deal with human bodies and non-transplantable body parts donated for education, research and the advancement of medical, dental and mortuary science.” If the bill passes the House, it will be introduced to the Senate for consideration. A similar bill, H.R. 1835, stalled in 2019.