This O.G. Embalming Text Is The Ultimate Guide to Mummification

Last week’s Friday Funeral Fast Wrap included a cartoon illustrating one of the dangers of offering services personalized to “fit every individual and family” …

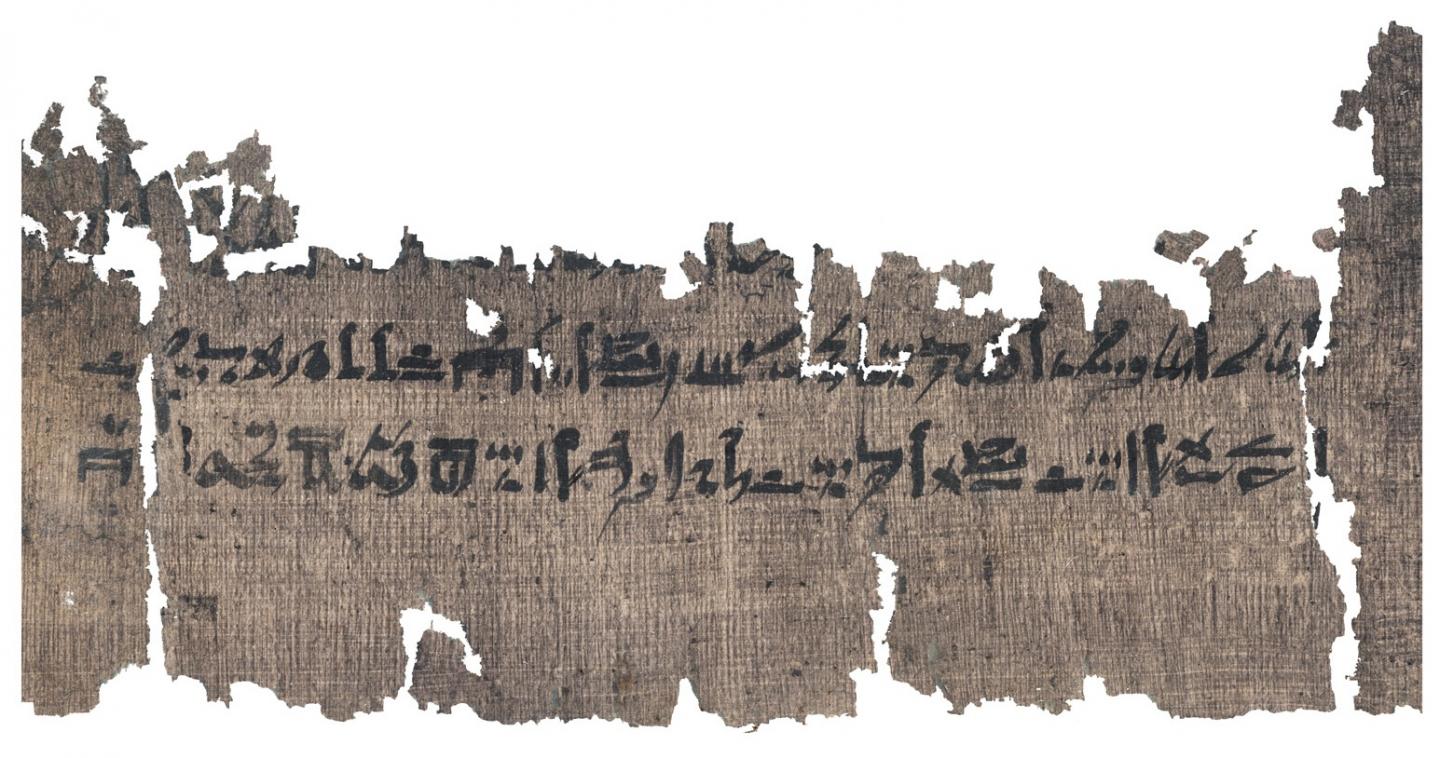

Oddly enough (we didn’t plan this, we promise), an amazing new interpretation of an ancient Egyptian papyrus surfaced around the same time as our cartoon. The text, written from 1424 to 1398 BC, is purported to be the earliest document providing step-by-step instructions for mummification. Thanks to the work of a Copenhagen University Ph.D candidate, the mummification manual will soon become available to anyone wanting to learn more about the process. Even funeral directors, we suppose.

Mummification primer

In its simplest description, mummification is an embalming technique. The process removes moisture from the body and uses natural preservatives to dry skin and organs. According to the Smithsonian, the earliest mummifications were accidental, as the dry sand and air of the Egyptian desert preserved bodies that were buried in shallow pits. Intentional mummifications in Egypt most likely started around 2600 BC and continued for over 2,000 years.

Popular culture would have us believe that mummification is a process exclusive to Egypt. In fact, archaeologists have found mummies predating those in Egypt in South America, Europe, and elsewhere. Egyptians just elevated the practice to an art form with their elaborate, intricate undertakings.

Another fallacy is that all Egyptians were mummified, which is far from accurate. The mummification process actually was reserved for only the wealthiest and most prominent citizens. Because it was considered a sacred art, very few practitioners existed. Egyptologists believe they passed their secrets to one another and subsequent generations orally. This fact makes the discovery of the embalming texts even more monumental.

70 days later

In general, Egyptian mummifications followed the same basic procedure. First was the removal of the brain tissue and internal organs, then the drying of the body, and finally, wrapping. University of Copenhagen Egyptologist Sofie Schiodt, who is editing the so-named Papyrus Louvre-Carlsberg text as her Ph.D thesis, describes the 70-day procedure as such:

The embalming, which was performed in a purpose-built workshop erected near the grave, took place over 70 days that were divided up into two main periods — a 35-day drying period and a 35-day wrapping period.

During the drying period, the body was treated with dry natron both inside and outside. The natron treatment began on the fourth day of embalming after the purification of the body, the removal of the organs and the brain, and the collapsing of the eyes.

The second 35-day period was dedicated to the encasing of the deceased in bandages and aromatic substances. The embalming of the face described in the Papyrus Louvre-Carlsberg belongs to this period.

The entire 70-day embalming process was divided into intervals of 4 days, with the mummy being finished on day 68 and then placed in the coffin, after which the final days were spent on ritual activities allowing the deceased to live on in the afterlife.

New information in the oldest text

Schiodt has also shared exciting new details from the text not found in the only two previously-unearthed mummification treatises. According to a release from the University of Copenhagen, Schiodt writes:

Many descriptions of embalming techniques that we find in this papyrus have been left out of the two later manuals, and the descriptions are extremely detailed. The text reads like a memory aid, so the intended readers must have been specialists who needed to be reminded of these details, such as unguent recipes and uses of various types of bandages.

One of the exciting new pieces of information the text provides us with concerns the procedure for embalming the dead person’s face. We get a list of ingredients for a remedy consisting largely of plant-based aromatic substances and binders that are cooked into a liquid, with which the embalmers coat a piece of red linen. The red linen is then applied to the dead person’s face in order to encase it in a protective cocoon of fragrant and anti-bacterial matter. This process was repeated at four-day intervals.

Mummy making … and more!

The mummification manual isn’t the only exciting discovery within the text. Schiodt has also found descriptions of medicines and illnesses and treatises on tumors. The herbal medicine study comprising the bulk of the six-meter-long papyrus focuses on one divine plant and its seed. It also thoroughly examines an illness of the skin the lunar god Khonsu allegedly sent.

A 2018 French preliminary translation of the text (available on Amazon) describes the “precision of the clinical observations” as “astounding.”

It includes maladies sometimes recognizable as conditions only recently diagnosed by modern medical professionals. These findings hint at the vast knowledge and wide range of expertise of these Egyptian practitioners. They seem to have mastered the art of clinical observation and tended to the elite both before and after death.

Although, according to PBS’s Nova, Egyptians stopped making mummies between the fourth and seventh century AD. Historians believe more than 70 million individuals were intentionally mummified in Egypt over a 3,000 year period.

We’re not exactly saying it’s time to bring mummification back. (Although there is actually one company in Salt Lake City, Utah that offers a modern version of the option.) However, if you want to gain that competitive edge locally, at least you’ll have access to the O.G. textbook. Just imagine the markup on sarcophagi!