Thailand’s First Serial Killer Si Quey Cremated After Five Decades on Display

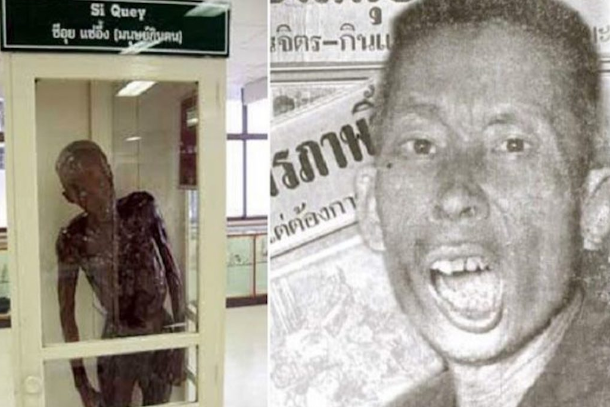

A Thailand museum cremated the body of the country’s first convicted serial killer in July, more than half a century after his death. Known as a “cannibal killer,” Si Quey died by firing squad in 1959 after authorities accused him of murdering several children and eating parts of their bodies. Since then, his mummified remains have been on display at Bangkok’s Forensic Museum, housed in a glass case and used by Siriraj Hospital staff to instruct medical students. In recent years, activists have sought to remove the body and give it a dignified burial.

Si Quey “The cannibal”

Si Quey was a Chinese immigrant working as a gardener in Thailand in 1958 when witnesses allegedly saw him trying to burn the remains of a missing eight-year-old boy. In a post-arrest confession, Si Quey supposedly claimed to enjoy the taste of children’s organs. The police then charged and convicted him of the murders of six other missing children.

Following his death, the Siriraj Museum embalmed and preserved Si Quey’s body in a display labeled, “Si Quey, Cannibal.”

His story, mythologized through the decades, has morphed him into a Thai bogeyman. Parents invoke his name to scare children away from loitering outside after dark.

Finally laid to rest

The claims around Si Quey’s crimes are dubious at best. Since he couldn’t speak Thai very well, police could only interrogate him through an interpreter. Records from the time period show rampant police corruption, the use of torture to elicit false confessions, and pervasive anti-Chinese sentiment that would have made a poor Chinese worker a convenient scapegoat for crimes.

Recently, over 11,000 people signed a petition asking the hospital to remove and properly bury his body. Wannapa Thongchin, Thap Sakae resident whose parents hired Si Quey as a gardener, supported laying the body to rest.

“We had to find a way to bring him out of the glass box,” she said at the funeral. Thongchin recounted how the museum display made Si Quey look tortured. “It made me feel sorry for him.”

His body was cremated in a state-funded funeral at the Wat Bang Praenk Tai temple, one of two temples adjacent to the Bang Kwang prison where Si Quey was executed. Si Quey has no known living relatives. However, a small crowd of human rights workers, prison officials, and curious locals gathered to witness the cremation.

The “Museum of Death”

Founded in 1888 after a global cholera outbreak, the Siriraj hospital and medical school is Thailand’s oldest and largest. With a capacity of over 2,000 beds, it sees over three million patients a year. The Siriraj Medical Museum, a seven-museum complex administered by the hospital, holds an impressive collection of medical oddities, pieces of forensic interest, and the preserved body parts of criminals and murder victims.

This “Museum of Death” offers up unusual anatomical conditions, parasites, foetuses, and other displays not for the faint of heart. The specimens serve as educational tools for medical students. However, in recent years researchers and museum administrators have begun to reevaluate the ethics of displaying human remains. Prior to his removal for cremation, the museum relabeled Si Quey’s body “Death Row Inmate.”

The gesture was a small acknowledgement of his dubious guilt.