Are Conservation Memorial Forests a “Better Place” to Spread Cremains?

It was during a 2015 cemetery visit when the seeds of Better Place Forests first took root in Sandy Gibson’s mind. Discouraged by the reflection of passing traffic on his mother’s gravestone, Gibson imagined there must be a “better place” to memorialize loved ones.

For Gibson, his business partners, and their investors, that place was a 20-acre privately-owned redwood forest three hours north of San Francisco, California.

A $12 million concept

Gibson’s idea was to create a series of conservation memorial forests along the West Coast. Families can bury the cremains of their loved ones at the base of a tree of their choice. Better Place then donates a portion of the plot purchase price to a land conservation trust. The family owns the tree in perpetuity, and the trust ensures that the tree is protected.

Gibson’s concept piqued the interest of investors, who contributed $12 million to the startup. Since opening the 20-acre property, Point Arena, in 2015, Better Place has developed and opened two more of its seven forests. Better Place Forests in Santa Cruz, California began accepting reservations for spots among its mountainous 80 acres in June 2019. The company’s newest property, 160 acres ensconced in the Coconino National Forest in Flagstaff, Arizona, is slated to open in 2020.

Better Place process

While Better Place does not offer cremation services, families can hold memorial services called “spreading ceremonies” in the forests. Prior to the service, Better Place mixes the cremains with “local soil and natural supplements” and digs a trench at the base of the selected tree. According to an October 2019 press release, more than 75,000 people have reserved a spot in one of the three Better Place properties. Each forest employs “forest stewards” to help families explore the property and pick out their perfect tree.

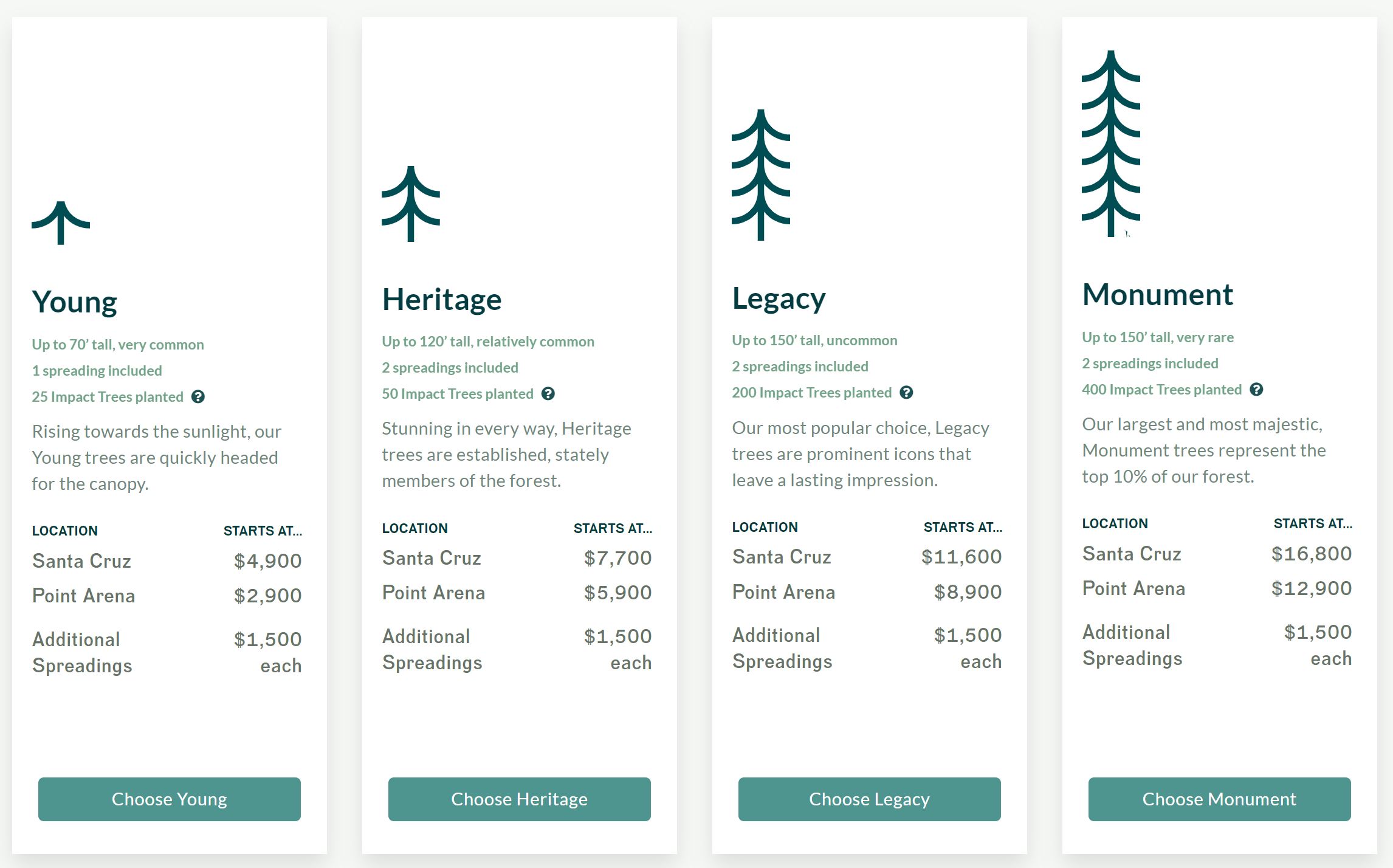

Pricing for plots is based on the location within the forest. This is similar to the varying pricing within different gardens or sections of a traditional cemetery. Cost is also contingent on the species and size of tree you choose. For example, one spreading under a common “Young” tree, which will grow to 70 feet tall, starts at $2,900 in the Point Arena forest. In contrast, two spreadings under a rare 150-foot “Monument” tree costs $16,800 in Santa Cruz, per the company’s website.

However, an article in Fast Company claims spreading cremains under an old redwood could cost up to $36,000. Also, Business Insider cites a “communal tree” option for about $1,000.

The inevitable criticism

As with any aspect of the death care industry, Better Place’s conservation memorial forest has drawn its share of criticism. In a January 20, 2020 Santa Cruz Sentinel guest commentary, resident John A. Mancini accused Better Place of taking advantage of families.

“The company is promoting a service, which is essentially free elsewhere, to emotionally vulnerable individuals at a greatly inflated price,” writes Mancini. In regard to the company’s fees, he added, “This is not dissimilar to a funeral home charging more for six inch padding in a coffin as opposed to three inch padding. The last time I checked I couldn’t find a sane person who claims to have communicated with the dead and been told the deceased prefers thicker padding or taller trees.”

State and national forests are also an option

Mancini says that the California State Parks Department allows the spreading of ashes in a state forest at no charge, regardless of the type of tree chosen. He’s right. The California Department of Parks and Recreation allows the scattering of human remains “where appropriate, in units of the State Park System.” Families must first complete an application detailing their scattering plans and selected location within the park. Restrictions warn against leaving containers, pieces of bone, or other recognizable forms to identify the cremains.

Many national forests and national parks have similar policies, including the Redwood National and State Parks organization, which manages four California redwood national forests. They cite Title 36 Code of Federal Regulations, Section 2.62(b), which simply requires obtaining permission prior to scattering cremated human remains. State and national forests don’t allow spreading in archaeological sites or Native American burial sites. However, there are no restrictions on specific tree species or sizes.

Many of these state and national forests specify that spreadings must be conducted privately. They do not allow commercial enterprises like funeral homes or crematoriums to supervise. They also don’t allow the placement of any memorial markers to commemorate the location of the cremains.

Disrupting the industry (?)

Better Place Forests is the first conservation memorial forest organization of its kind. Based on its lucrative profit potential and attention from the “green” community, it probably won’t be the last.

Environmentalists praise the Better Place concept for its land trust structure and partnership with nonprofit One Tree Planted. With each Better Place plot purchase, One Tree Planted will plant a number of “impact trees” in the forest. “Young” tree plans finance the planting of 25 impact trees, while a “Monument” purchase plants 400.

Some believe the forest is an affordable alternative to purchasing a cemetery plot. Even back in 2000, a San Francisco newspaper opined the cost of dying in the city. “Nowadays, it’s tough finding grave sites under $2,000,” the article read. “Some family plots on the Peninsula fetch as much as $265,000.”

Investors are excited about the potential of “disrupting” a “broken” industry. “The death services market is very big – US$20 billion a year – and customer approval is low,” Jon Callaghan told Business Times in June. Callaghan is a partner at True Ventures, an investor in Better Places.

This all bodes well for Better Place founder and CEO Gibson, who doesn’t hide his feelings for cemeteries.

“Cemeteries are really expensive and really terrible, and basically I just knew there had to be something better,” Gibson told Better Times. “We’re trying to redesign the entire end-of-life experience.”