Obit for the Obits

Article originally from: NY Times

No sense in burying the lede. This week, after more than eight years of lively habitation in one of journalism’s more obscure corners, I’m making a final egress, passing on. Starting after Friday’s deadline (ha!) I am an ex-obit writer.

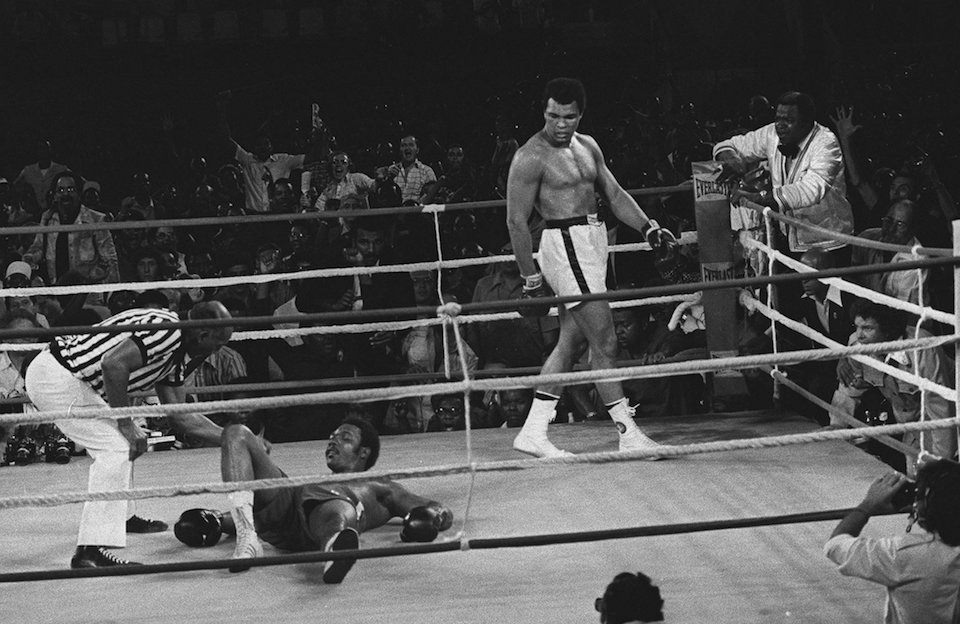

Here’s my legacy. A thousand salutes to the departed, something like that. Age range 11 to 104. Cops and criminals, actors and athletes, scientists and judges, politicians and other poobahs. Famous, infamous or as obscure as the rest of us except for one instance of memorable distinction. A man with a mountain named for him, another who hijacked a plane. A woman who changed infant care for the better, another who shot a ballplayer. High achievers who died after long and fruitful lives (Yogi Berra, Ruby Dee, E. L. Doctorow) or whose unanticipated demise (Grete Waitz, Philip Seymour Hoffman, David Carr) demanded furiously quick reporting and writing — and attention on the front page.

Name a profession (Scream queen? Used car dealer? Astronaut? Guru?) or an achievement (Solved an equation? Caught a killer? Integrated a sitcom?) or an ignominious label (Pederast? Con artist? Embezzler?). For whatever reason — AIDS or Alzheimer’s, cancer or a car crash, heart failure or kidney disease, sepsis or suicide — they all went on my watch.

We’re accustomed, my colleagues and I, to saying that an obituary is not about a death, but a life. This is true, but really, we’re reporters and you can’t avoid the news, which is, of course, the same news every time. That’s one thing that distinguishes writing obituaries from anything else in journalism.

Another is that we start at the end and look backward. There’s some reward in this, in the excavating we do that often unearths interesting, long-forgotten facts.

But it’s melancholy, too. We had a movie made about us recently, a documentary called “Obit,” and in it my former deskmate Doug Martin, who effected his own exit from the obit business a couple of years ago, made a comment of encapsulating rue. He often admired the people he wrote about, he said, but he never got to meet them.

I’ve had a long career at this newspaper, three decades, exercising, for better or worse, a good deal of imagination. But in the last eight-plus years I haven’t had to come up with a story idea. I’ve spent hundreds of afternoons burrowing deep into cyberspace and perusing yellowed news clippings from The Times’s historical archive, a.k.a. the morgue. And then the phone interviews — necessary, sometimes grueling, often poignant with laughter or tears, half consulting with and half consoling friends and relatives of the dead who hope I’m giving credence and gravity to their anguish and not sucking the marrow out of it.

I hardly ever left the office; that bugs me. A few trips to the library or a bookstore, once or twice to a museum, the apartment of the widow of a former Marlboro Man who had some old ads I wanted to see. Not the most adventurous reporting in the world.

All that said, I don’t think it’s self-aggrandizing to say that obituary writing is important work. An obituary is, after all, the first last word on a life, a public assessment of a human being’s time on earth, a judgment on what deserves to be remembered. In addition, though we write for readers of all stripes, of course, and not especially for those in mourning, I suspect all of us who do this keep the loved ones in mind, and if we don’t seek their approval exactly — unsavory details are often unavoidable — we strive to write so that they at least recognize the person they’ve lost. Journalism isn’t supposed to be a personal service, but obituary writing, without compromising any professional integrity, can be. Maybe should be. In any case, getting it right is not easy. And getting it wrong can cause real distress to the already distressed.

Obituary writers tend to be older people, at least at The Times, where the average age of the reporters and editors on the obits desk is higher than that of any other department. This is as it should be. Partly, I guess, they don’t want us running around too much, approaching decrepitude as we are. But mostly it’s because we’ve shared a lot of time on earth with our subjects and have lived through much of the history they helped make. Not incidentally, we’ve all had the experience of grief and know what it feels like to live in the immediate aftermath of personal tragedy.

The significant irony to retiring from the obits department is this: I may be going but you’re not quite rid of me. My byline is likely to continue to appear for months, even years, because of the 40 or 50 obituaries I’ve written of people who are still living — the future dead, as we say, in mordant obit-speak. Perhaps I’ll even have a posthumous byline or two — not something I aspire to, by the way.

Advances are what we call these obituaries written in, well, advance. It’s a practical matter; you can’t write the comprehensive life story of a president or a pope or a movie star in an hour or even a day. But think about the presumption of such an enterprise. We know they’re going. We don’t know how. We don’t know when.

Which is, of course, the main reason I’m getting out while the getting is good.

Bruce Weber, an obituary writer for The New York Times, is the author of “Life Is a Wheel: Memoirs of a Bike-Riding Obituarist.”