In Praise of Social Media Mourning

Originally article from Slate.com

The death of a major artist reveals what’s best about Twitter and Facebook, not what’s worst.

By now you know the social media celebrity-death protocol. As the news spreads there’s a rolling wave of “oh no”s and “RIP”s—many of them omitting the name of the deceased, to mark the advent of a topic so urgent that everyone can be assumed to be participating. Then come the tributes: personal memories, 140-character career summations, expressions of sadness.

And then come the complaints. These tributes, we are told, are “performative.” To post a response to the death of a famous stranger is to “make it about you.” A sharp tweet from 2014 gets retweeted back into circulation at these moments: “but how does this affect Me, the Protagonist of Reality.”

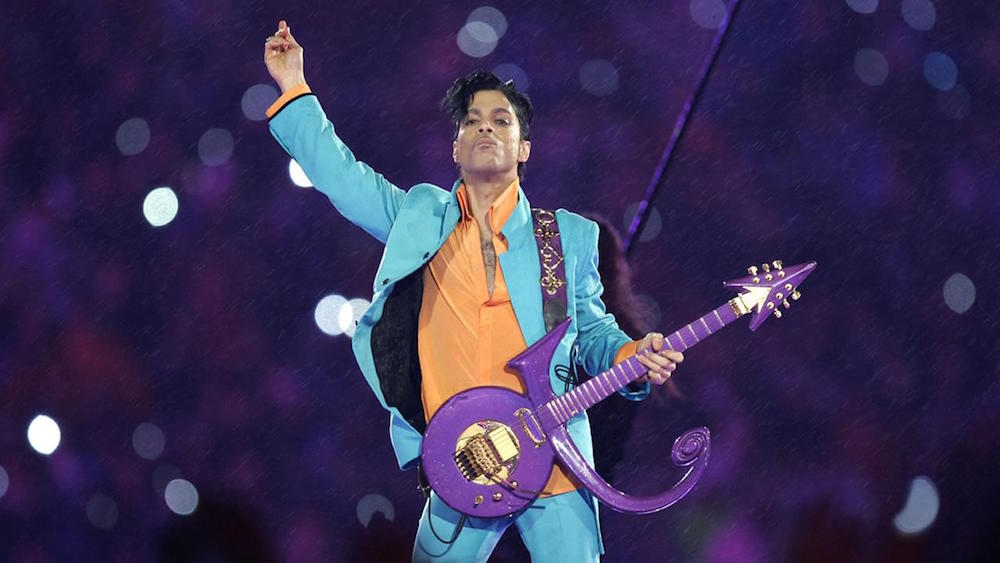

Since 2016 began we’ve seen the deaths of two titanic pop music figures, the kind of events that stop the cultural traffic for days. And between David Bowie and Prince came Alan Rickman, Glenn Frey, Maurice White, Umberto Eco, Harper Lee, George Martin, Keith Emerson, Phife Dawg, Garry Shandling, and Merle Haggard. The responses to this remarkable streak of quietus—especially the three-day virtual wake for Prince—made me realize that complaints about narcissism and performative grieving are wrong: celebrity-death Twitter (and Facebook and Instagram) are changing the way we memorialize artistic figures, for the better.

To state the obvious upfront: There’s a difference between losing someone you know personally and losing someone you know only through his or her work. I think everyone is clear on this distinction, including the people who tweeted about how sad they were when Robin Williams died. (Williams’ death in 2014 inspired an especially sentimental response that helped put internet mourning on the map.) If you want to reserve the word grief for the more personal kind of loss, I won’t begrudge you that.

But the two are related, if only analogically. Grief is work—the painful work of reconfiguring one’s internal world to accommodate a sudden absence. The death of a significant artist requires a similar rearrangement, although the work is a lot more enjoyable. We have to move the deceased’s account from the column of the living to the column of the dead. He is no longer a candidate for greatest living anything. His work now belongs to a fixed moment in history. The arc of his career can at last be assessed and argued over.

Before we were all wired together into this huge, keening, pretentious macroconsciousness, the process of determining how an artist would be remembered began with TV news reports and commemorative issues of mass-circulation magazines, i.e., the shallowest and most vapid channels of the mainstream media. Things were not better then. Imagine the montages that aired on the night of Dec. 8, 1980: The Ed Sullivan Show, the screaming Beatlemaniacs, the Bed-In for Peace, the same footage on every channel, all set to “Imagine.” It’s a process that reduces an artist to a few familiar images and greatest hits, constructing a cardboard cutout and presenting it to posterity for consideration.

Whereas within a few days of Prince’s death, I read the first thoughts and associations and memories that he inspired in hundreds of people. Some of the Prince-related ideas I gleaned from Twitter and Facebook during that time: that for many people Prince was implicated in the first association of sex with pleasure; that people who don’t usually dance could dance to Prince’s music with uncharacteristic confidence; that Prince once made a crowd wait a full hour before coming out for an encore; that middle-aged women were among the first to perceive Prince’s unconventional sex appeal; that at least one parent used Prince as an example of how much could be accomplished through diligent study; that more than one short person took pride in the fact that Prince was also short.