Undertaker Thomas Lynch On How American Memorials Went Wrong

Article originally was published on BostonGlobe.com

THE TRADITIONAL American funeral, as we tend to think about it, was a somber affair. Mourners listened to their priests, ministers, or rabbis eulogize the dead, and then physically engaged in the process of burial—carrying the casket or perhaps shoveling dirt on the grave.

As religious connections have frayed, and our desire to confront loss has waned, the funeral service has changed accordingly. Jessica Mitford’s book “The American Way of Death,” with its chronicles of greedy undertakers and overpriced caskets, played a prominent role in the changes as well. In recent years, many Americans have chosen to transform funerals into celebrations of life, with reminiscences and funny anecdotes shared by family and friends taking the place of religious ritual. With cremation now replacing burial in almost half of American deaths, even the body itself is increasingly absent.

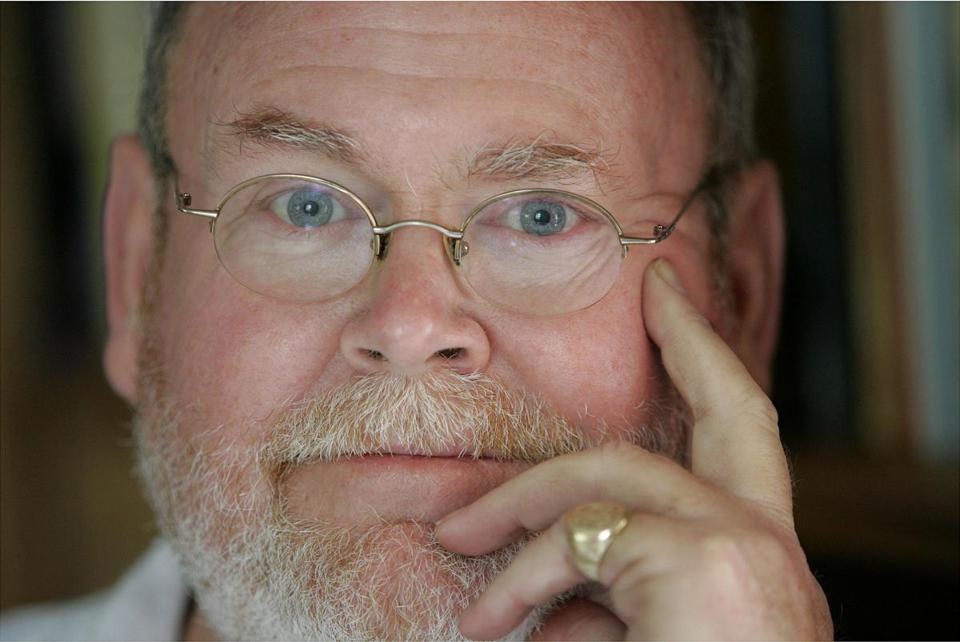

Thomas Lynch, an undertaker and poet, and the author of the acclaimed essay collection “The Undertaking: Life Studies from the Dismal Trade,” believes that in adopting these newer rituals Americans have lost something important. In a new book, “The Good Funeral,” written with theologian Thomas G. Long, he makes a passionate argument for a return to the labor of the funeral—to the presence of a body and to mourners playing a role in the physical disposal of their dead, be it through burial or cremation.

For Lynch, a “good funeral” offers not just a chance to remember the dead, but to acknowledge the permanence of our loss. We find it, he suggests, in the “hard duties” of tradition, primarily the shepherding of the body to its final resting place. “By getting the dead where they needed to go,” he writes of funerals past, “the living got where they needed to be.”

Lynch spoke to Ideas from his home in Michigan.

IDEAS: What changed in the American way of death for the memorial service to, in so many cases, replace the funeral?

LYNCH: In the funeral home, I think the emphasis was placed on the boxes—on caskets, and burial vaults, and the stuff rather than the substance. I think people quite properly saw that most of the costs were associated with the dead body’s presence at the funeral. Because of that, more and more of them started opting out of that, or a much reduced presence of the body….[A]t the same time, cremation was becoming less the exception to the rule and more the rule itself. We have shifted away from the sacred, away from the deeply human event, to these kinds of silly events that have little or nothing to do with the dead. I really wanted to make the case for the corpse. Because we are all going to be corpses one day.

IDEAS: Your coauthor is a minister. What about those who might say that religious ritual simply does not speak to their lives?

LYNCH: I was sitting in Ireland back in ’05, when the pope died, and seeing the corpse of the pope on the front pages, I thought, “I know that the response to this will be ‘how very Catholic,’ or ‘how very Polish,’ or ‘how very Italian.’” But I think of it as “how very human.” I think these duties we have to the dead do not proceed from our Christian mindset so much as our human condition. I think of our religiosity proceeding from our mortality. I mean, why would you bother with religion if you didn’t have to consider what happens after life?

IDEAS: Can you have a “good funeral” without a religious component?

LYNCH: I’ve certainly been to a lot of funerals where the belief was not Christian or orthodox in any way. It didn’t have a higher religious component, but it did have a sense of duty to the dead, and the living felt more alive after they had done those things.

IDEAS: Is there a distinction in your mind between a graveside funeral and a cremation?

LYNCH: I see the fireside and the graveside as equivalents. That’s where we should go with them. To the edge of whatever oblivion we’re consigning them to. Whatever that space is, it’s made sacred by the fact that we’re putting our dead in it.

IDEAS: Why is this body-less funeral primarily an American phenomenon?

LYNCH: I think Americans figured out that if you can dispatch the body, it is more convenient, emotionally, spiritually, and financially. It’s easier in the near term.

IDEAS: And in the long term?

LYNCH: My father had it right when he said, “You can pay the shrink, you can pay the bartender, or you can pay the funeral director.” The dead are going to exact their pound of our spiritual and emotional flesh. And I think one of the things that makes it more bearable is if we do our duty to the dead….The blowing of bubbles or the balloon launch or the duck release, it’s all very nice. But this effort to personalize funerals based on people’s pastimes and their hobbies is so lightly weighted that we don’t feel like we’ve done real work.

IDEAS: What, then, gives the good funeral its weight?

LYNCH: If you have a bunch of people gathered around an open piece of ground, and you lean [a shovel] towards someone, you don’t have to give them the operating instructions. They know what to do with it! This is coded right in our genes as humans. I mean literally, we are part of the humus. This is us. We are people who dig holes in the ground and fill them.

It’s the hardest thing you’re going to do, to carry and bury the body of someone you care deeply for, or are long associated with. Because when we bury someone like that, we’re burying part of our history, too. But when you do it, you feel, “I did what I could. Someone will do it for me.”