Rewired by Loss: Grief Is Essentially a Brain Injury

That’s right – a brain injury.

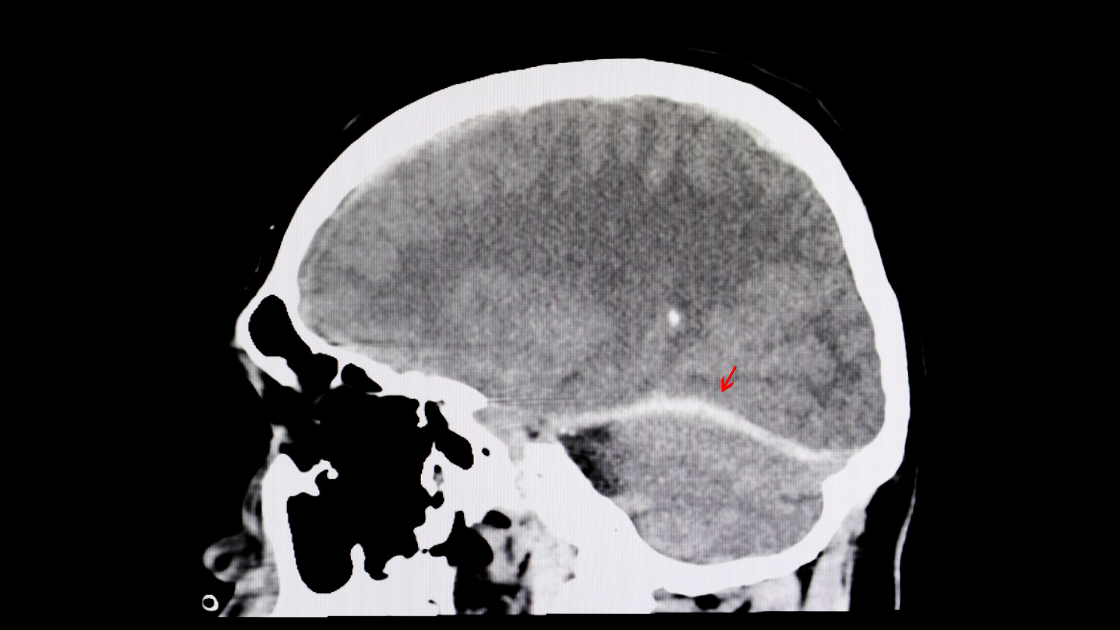

A number of scientific studies reveal that an emotional disturbance, such as that caused by the experience of grieving a loved one, creates a functional disability in the brain, especially in situations of losing one’s spouse.

Somewhat as a stroke might do, the resulting effects rewire the brain in a lasting way to accommodate the changes caused by enduring grief.

What Qualifies as a “Brain Injury”?

There are a couple of ways traditional brain injuries are classified – traumatic brain injuries, or TBIs (car accidents, gunshot wounds) or acquired brain injuries, ABIs (lack of oxygen, electric shock, seizure).

The effects of emotional stress on brain function, particularly those of complicated grief, disrupt brain cell (neuron) performance to a degree on par with an acquired brain injury (ABI).

According to The Brain Injury Association of America, neurons connect or disconnect in response to the duration and intensity of an extreme emotional response. Neuroplasticity – the changeable quality of the brain which allows it to generate new cells and alter connections of existing cells – is how our brains adjust to life-altering events such as trauma, loss, injury, and illness.

It’s a survival technique that allows us to adapt to new circumstances… such as learning to navigate everyday life and the world without your spouse, child, or loved one.

A Little Stress Can Be a Good Thing

Loss is stressful, but stress at manageable levels provides some benefits. Reducing fear, improving the memory, and increasing nerve growth are effects of tolerable stress that can be helpful in survival situations.

The effects become less of an asset and more of a liability, however, when the stress stimulus is too strong over time. When great stress poses a relentless, ongoing onslaught on day-to-day experience, its effects become entrenched and harmful. Changes in brain function may become pronounced in diverse areas including decision-making skills, memory, and attention. Visuospatial function, verbal fluency, even the rate at which one can process information could also be compromised. A 2019 paper from the journal Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience revealed that those going through profound grief tended to deliberately restrict their own consciousness of the loss they’d endured. The objective was specifically to think less about the loss. As a result, the grieving experienced increased levels of anxiety and decreased ability to focus, a kind of “brain fog”.

And as the adjusting brain’s new “coping mechanisms” last, eventually they “hard-wire”, creating a default setting. In this way, such “adjustments” reinforce themselves until they become the grieving brain’s new normal.

Are All Grieving Brains Alike?

Studies have shown activation of certain brain structures during the process of deep grief: the prefrontal cortex, the amygdala, the anterior cingulate cortex, the posterior cingulate cortex, and the insula. The suggest a complex of areas of the brain that correspond, potentially to “generate the symptomatology of grief.”

As loss and grieving are at the core of the human experience, understanding the ways that these experiences affect the health of those who endure them will make more effective support of survivors possible.

Hopefully, such studies into the variabilities of grief’s effects on the mind as well as the heart will help us to learn more and strengthen what we already recognize of grief’s various kinds of manifestation, particularly the ways it may complicate other aspects of health.

The more we understand grief’s nature, the better our chances of creating supportive measures to assist and heal the bereaved. And the more we know, the better our chances of arresting the advancement of even more serious health problems.