Visit a Replica of America’s First Crematory

Inside an unassuming building just off Interstate 45 in Houston, Texas, home to the National Museum of Funeral History, stands a life-sized replica of a small brick building, the function of which ignited a national controversy about religion, hygiene, and land use.

With over half of Americans choosing cremation as their disposition option today, it’s easy to forget that the practice was once seen as barbaric and sacrilegious. While burning the dead dates back thousands of years as one of humanity’s oldest funerary practices, 19th century Americans found the practice abhorrent and uncivilized. When Dr. Francis Julius LeMoyne proposed the nation’s first crematory in the late 1800s, he met with vicious resistance from community members and religious leaders, many of whom viewed cremation as “a sudden, ruthless and cruel obliteration of the dead” that stripped away the spiritual depth of a traditional funeral.

A practical question

Part of LeMoyne’s argument, now largely debunked, was that ground burial led to harmful contamination of surrounding soil and groundwater, leading to outbreaks of cholera, yellow fever, and other diseases. Another concern, the use of precious urban land for cemeteries, has grown even more relevant. An often-quoted 1887 pro-cremation treatise by Hugo Erichsen estimates that half a million acres of “the best land in the United States” would be swallowed up by cemeteries in just a few years, calling the prospect “an outrage.”

Touted as a modern and sanitary alternative to burial, cremation would also eliminate the need for expansive cemeteries, which were falling out of favor as urban real estate grew in value. In 2020, many urban cemeteries in the U.S. have stopped accepting new burials, and American graveyards have seen a history of displacement and relocation as urban development ploughs across old neighborhoods.

‘As unaesthetic as a bake-oven’

Rejected by a local cemetery, LeMoyne built his crematory on his farm in Washington, Pennsylvania. Modeled on a working demonstration at the 1873 Vienna Exposition, the building measured 20 by 30 feet, cost $1,500 to build, and featured a reception room and furnace room. LeMoyne’s design created intense heat, with the flames never having to touch the body.

Some visitors found the simplicity of the building “repulsively” plain, “as unaesthetic as a bake oven.” A popular minstrel show portrayed the “cremationists” as ruthless and disrespectful to the remains of the dead. Yet others cheered the arrival of the ultra-modern method, and LeMoyne had several bodies waiting on ice by the time his crematory was completed.

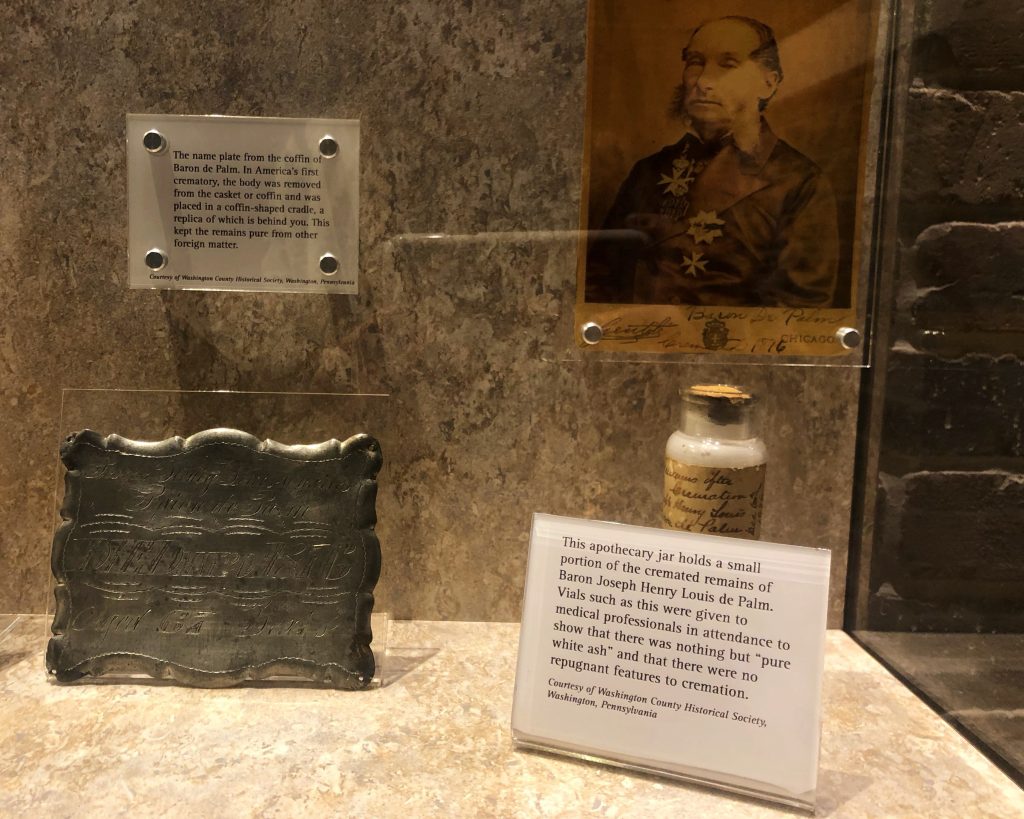

LeMoyne, who offered free cremation to promote his invention, found a willing first participant in the Austrian Baron de Palm. Newspapers from across the country clamored to cover the event, coming away with mixed impressions. The cremation, which took about three hours, was witnessed by a throng of journalists, neighbors, and curious onlookers.

A New York Times dispatcher, upon getting a glimpse through the peephole into the furnace, wrote that, after the two and a half hour process, the Baron’s body was “a mere structure of powdery ashes, which the lungs of a child might blow away.” The dispatch also mentions the cost of the fuel for the cremation, $7.04—major savings considering that a traditional funeral in the 1880s cost around $100.

Slow growth

Religious stigma at first hindered the growth of cremation, but cremation societies started organizing to convince the reluctant public and reduce the taboos around what they perceived as a clean, scientific, and practical disposition method. The variety of economic, social, public health, and environmental arguments of the pro-cremation movement drew a broad range of activists to its ranks. Cremation, they claimed, would reduce the disparities between rich and poor that were already apparent in 19th century America, protect groundwater and soil from contamination, and end the wasteful use of urban space for ground burials.

In his treatise defending cremation, LeMoyne addressed religious concerns, using Bible verses to argue that the physical body wasn’t really of any consequence, and that spending exorbitant amounts on elaborate funerals and expensive burial plots were sins of vanity. By the early 1900s, the practice lost its sensationalism, and in 1963 the Vatican officially approved cremation as an appropriate disposition, opening the door for millions of Catholics who had until then believed that a physical body was necessary for Resurrection.

Today, the cremation industry is being once again revolutionized by a growing community of artists and entrepreneurs creating unique, meaningful ways to display, store, and engage with the ashes of loved ones. From pressing ashes into diamonds or vinyl records to sending them on journeys into space or the ocean, these businesses are developing entirely new options for memorializing the dead.

The original LeMoyne Crematory, which ended operations in 1901, still stands today, preserved as a monument to Dr. LeMoyne’s vision.