A “Useful Corpse”: Body of Shady Bigamist Used to Promote Funeral Home in 1902

The rising popularity of cremation has brought with it an interesting conundrum: unclaimed remains. With traditional burial, disposition of individuals with no family or funds is managed and paid for by local governments or organizations. Unlike cremains, bodies aren’t usually left in a back room until someone comes along to claim them. That wasn’t the case in 1902, though — at least in one instance. When no one could prove the identity of a dapper stranger who died penniless in an Asheville, North Carolina boarding house, the funeral home decided to use his “fine, handsome corpse” to their benefit. As fascinating as his post-death existence became, it eventually paled in comparison to his tall-tale-like life story.

An unusual opportunity presents itself

When Asheville undertakers Brown, Noland & Co. took possession of the tuberculosis-ridden body of a 30-something-year-old man, they knew him only as Charles H. Asquith. Months earlier, he had presented himself to the local hotelier as a wealthy Englishman in need of a physician’s care, which was quickly arranged. Local doctors and nurses tended to the man in the boarding house around the clock until he expired. The undertakers embalmed Asquith, dressing him in “evening dress, with silk hat and walking cane.” Cablegrams were sent to Asquith’s supposed family members, but months — then years — passed with no reply.

At some point, the folks at Brown, Noland & Co. realized they could use Asquith’s languishing corpse to advertise their embalming skills. Like the doctors and nurses, the undertakers remained unpaid for their services. Making the best of the situation, they built a glass cover for Asquith’s coffin and invited locals to view him. According to newspaper reports of the time, the body “became almost petrified, losing little of its lifelike appearance, and was exhibited in many side shows.”

Will the real Asquith please stand up…

In 1905, the undertakers received a letter from Lady Douglas of Lambert’s Point, Virginia, in which she claimed to be the wife of the deceased. She said that based on the widely-circulated description of the corpse it was likely that of her husband, English nobleman Lord Douglas. Only a few months earlier, a banker visiting from Waco, Texas said the body looked like that of a man who had swept through his town selling powder that supposedly prevented gasoline explosions.

By May of 1907, “several women from different portions of the union” had traveled to Ashville to view the body, “claiming it as their husband and asking to be allowed” to take it away. Authorities, however, were at the same time starting to puzzle out the man’s identity. One newspaper announced that the body, which “stands on a pedestal as an advertisement for an Asheville undertaker,” was that of Sydney Lascelles, “one of the smoothest swindlers in history.”

The many lives — and wives — of the mysterious man

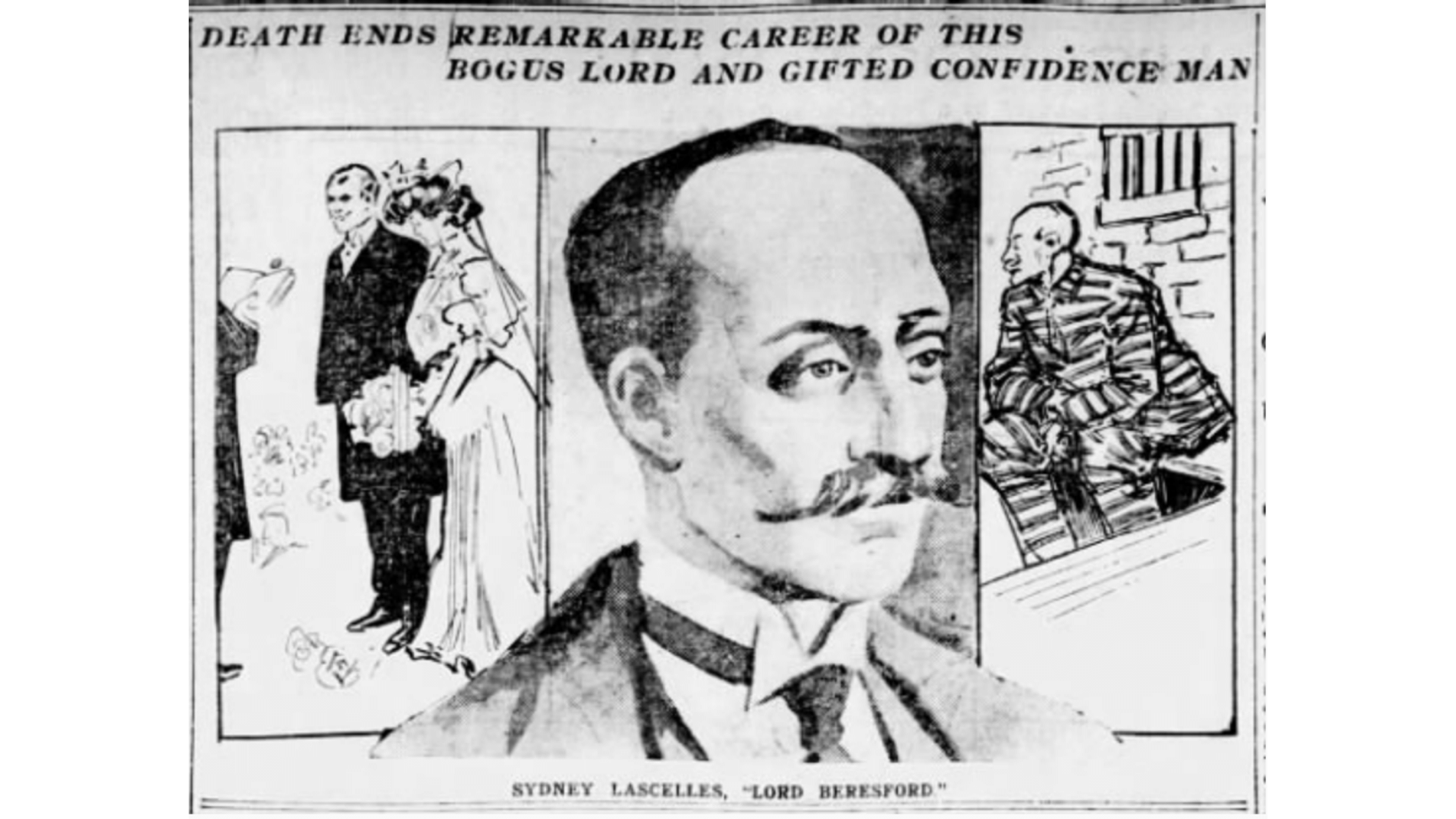

The story of Sydney Lascelles, as told by an attorney from Rome, Georgia, became more and more unbelievable as it unfolded. The lawyer said he had represented Lascelles “during his several trials” in Rome on “various criminal charges” years earlier. He revealed that Lascelles had for years assumed the identity of Lord Beresford, and “with all the pomp and ceremony and cockney talk befitting one of his supposed position in the financial world” had swindled large firms — and at least 16 wealthy wives — out of “large sums” of money.

The “bogus Lord Beresford,” the attorney explained, had used his looks, charm, and the name of a real English lord to cultivate relationships with rich and powerful “society people.” He even had the Beresford coat of arms imprinted on “his private checkbook on the Bank of England.” Of course, these checks weren’t backed by actual funds, so before the recipient could cash them, Lascelles would disappear “between suns” with swindled goods and “diamond rings and other tokens loaned him by society damsels.”

Wife No. 1

It’s possible that Lascelles’ true identity and his checkered past proved even better for the business of Noland, Brown & Co. than their embalming prowess, for they kept the “mummy” on display for another three years. In 1910, though, a woman claiming to be the sister-in-law of Lascelles’ “wife No. 1” (as the newspapers referred to her).

Mrs. T.J. Summerfield of New York explained that Lascelles had secretly married her wealthy young sister-in-law without the consent of the wife’s mother. The mother had disowned the girl after giving the young couple an allowance of $10,000, which they used during a three-year stay in Europe. When they returned home, Lascelles promptly slipped away, leaving the girl in her parents’ care.

Upon learning the true identity of the Asheville corpse, Mrs. Summerfield paid the $110 funeral bill and arranged for the body to be shipped to Washington, D.C. for cremation. She explained that she was planning to move to Asheville, and “could not bear to have her brother-in-law kept in an undertaker’s place unburied.”

“Enshrouded” in mystery

You might think this would be the end of the tale of Sydney Lascelles. Unfortunately, no. In August of 1910, a New York newspaper reported that after the cremation in Washington in May, the location of the ashes of the “petrified lord” was a mystery.

“Whether his ashes are still in a mortuary chapel or were taken away by a mysterious woman who is said recently to have visited Washington, is an unanswered question,” read a story in the Yonkers Herald Statesman.

It seems that around the same time Lascelles’ body arrived in Washington, so did a young woman calling herself “Mrs. Thomas.” The newspaper reported the woman visited the mortuary several times after Lascelles’ cremation, but “suddenly left the city, owing, it is believed, to publicity concerning the disposition of the remains.” The article goes on to speculate that “Mrs. Thomas” was one of the “numerous women whom Lascelles deluded into a bogus marriage.”

After the reported disappearance of Mrs. Thomas and her bogus husband’s ashes, Lascelles’ name and story faded away as a footnote in history — and a funeral home marketing approach that truly should never repeat itself.

Newspapers cited for this article, accessed via Newspapers.com, include the Asheville (NC) Citizen-Times (14 Jul 1905, page 8), The Chattanooga (TN) Star (9 May 1907, page 1), the St. Louis (MO) Post-Dispatch (11 May 1907, page 5), The Washington (DC) Post (20 May 1910, page 1), The (Oneonta, AL) Southern Democrat (26 May 1910, page 2), The (Centre, AL) Coosa River News (3 Jun 1910, page 4), The Bedford (IN) Daily Mail (18 Aug 1910, page 3), and The (Yonkers, NY) Herald Statesman (29 Aug 1910, page 1).