Funerals During the 1918 Flu Pandemic

Overflowing morgues. Caskets piled in the streets. Cemeteries running out of space. Amid the 1918 flu pandemic, the breakneck speed of the disease forced families to forgo formal burials, overwhelmed casket manufacturers, and upended American funeral traditions.

Familiar cultural rituals help us maintain a sense of normalcy. Take these away and society quickly loses hope. The stress and uncertainty that come with the loss of ritual can have devastating psychological effects. During times of pandemic, funeral directors are thrust onto the frontlines of the battle against disease and death, with their services proving even more valuable when the familiar aspects of society begin to break down.

An enemy on the home front

The world was already at war when the flu began killing—first soldiers, then everyone else: young, old, sick, and healthy. By the time it was over, the 1918-1920 pandemic killed ten times more Americans than the Great War and at least 3% of the world’s population.

Recent advances in transportation technology had just made the world more connected than ever before. The flu, like a deadly hitchhiker, traveled unencumbered across the globe, ravaging communities already affected by war and killing more than 50 million people worldwide, with some estimates ranging as high as a hundred million. Americans, only just accustomed to embalming and professional funeral services, had to once again face the visceral reality of death on their doorstep. Carefully calibrated systems broke down, and the sheer number of deaths overwhelmed the funeral industry along with everyone else. The flu reached into almost every household, spreading panic even faster than the disease itself.

“Garages full of caskets”

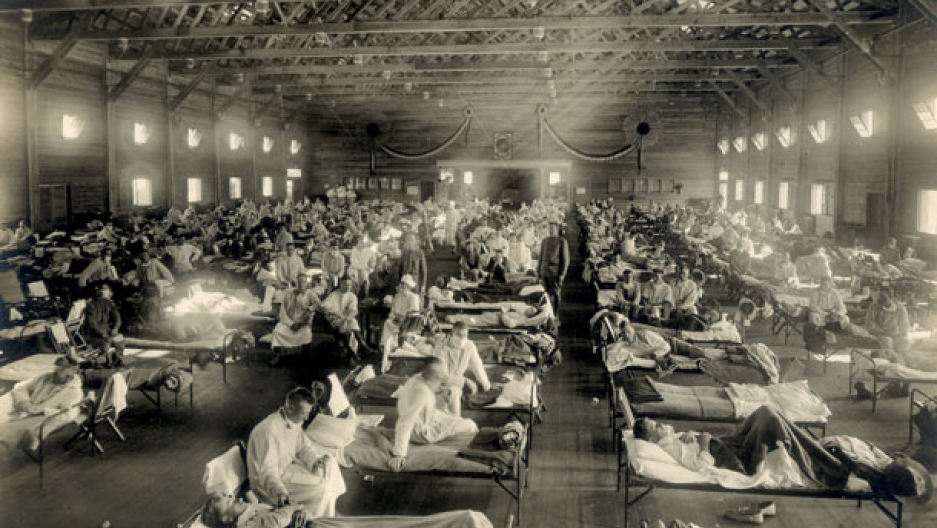

The pandemic took people by surprise and shook America’s newfound faith in medical science. The speed and ferocity of the virus was like nothing anyone had ever seen. Philadelphia’s city morgue, built with the capacity for thirty-six bodies, at one point overflowed with five hundred corpses. Funeral homes suddenly found themselves overrun with clients.

Because cremation was not yet popular, families often kept bodies at home. They covered them with ice to stave off decomposition until burial could take place. The demand overwhelmed the nation’s embalmers and casket builders.

When normal funerals became impossible, cities began to send patrol wagons to collect the bodies of the dead. Cemeteries continued conducting burials with a reduced workforce when gravediggers and undertakers themselves got sick or were afraid to go to work. Cities called in their employees, inmates, and sometimes the families of the deceased to dig the graves. In Kentucky, miners shifted from digging for ore to digging graves.

Already busy supplying thousands of WWI funerals, funerals, casket manufacturers couldn’t keep up with demand. Poor families had to bury their dead in mass graves, without coffins or ceremony. Desperate families resorted to burying children in cardboard macaroni boxes.

The ghastly cost of the disease was visible on porches and street corners everywhere. Caskets piled up in front of mortuaries and homes, waiting their turn.

“Spit spreads death”

Government regulations soon mandated burials for influenza victims within 24 hours of death and prohibited public gatherings, including funerals and wakes. Like today’s social distancing guidelines, the ban on public gatherings took an emotional toll on Americans. Recently united by the war effort, they had grown used to depending on their neighbors and friends for strength. Yet rapid local response proved crucial in containing the epidemic and slowing the rate of infection and death.

Today, unmarked mass graves from the 1918 pandemic are still being uncovered, and we may never know the final resting place of many hastily buried flu victims. The pandemic struck at the core of society, ripping through the heart of American cities and disrupting essential industries, habits, and rituals.

Haunting images of overflowing hospital wards, pedestrians wearing masks, and coffins piled high remain etched in our consciousness. Yet, the lessons of the 1918 pandemic have eluded us. When it comes to public health, “historical knowledge is power.” The social distancing policies undertaken then and now are the first and most effective step in fighting the spread of a powerful new virus. Then, like now, protecting the vulnerable from infection required sacrifices from every part of society.