Death Porn

This article was originally published on CalebWilde.com

There are two ways you can look at death as being pornographic. In the one sense, pornography is representative of something taboo. In the Victorian era sex was a taboo subject. Today, as some have argued, death is the new taboo … a taboo that we make a huge amount of effort to deny. Anthropologist Geoffrey Gorer said, “At present, death and mourning are treated with much the same prudery as sexual impulses were a century ago.”

Richard Beck wrote,

“the American success ethos is, at root, a neurotic defense mechanism involved in repressing death anxiety. The American culture is, thus, largely delusional and fictional, characterized by a fundamental dishonesty about our mortal condition. Americans pretend that they are immortal and have “all the time in the world.” Consequently, anything that punctures this illusion–disease, decay, debility or death–is pushed aside and avoided as unseemly and illicit. Hence the label “the pornography of death.”

Death as taboo pornography.

But there is another kind of death porn. Another way death and pornography are related. This other way isn’t through representation but through analogy.

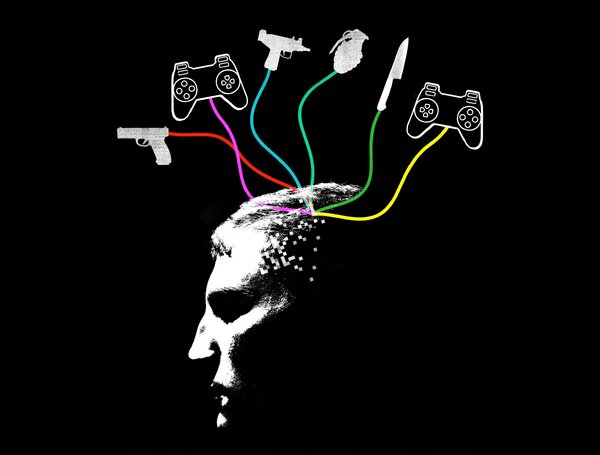

Porno films have an intrinsically depersonalizing effect on those involved and those who watch. This commodity of sex has been shown to effect real life relationships in a variety of ways, most of which tend to be harmful. Just as “sex as commodity” can become harmful so can “death as commodity.”

Have you ever wondered why you can watch a gratuitous amount of violent deaths on TV and not be too particularly bothered by it? I’ve never lost sleep over a death on a TV show (although it was difficult when Lori died on The Walking Dead. And the Starks in Game of Thrones).

We play Black Ops on our game console and kill a couple dozen persons in one sitting without thinking about the fact that we are playing a game (A GAME!) where the objective is to kill as many people as we can. And the best gamer is the one who can kill the most.

We watch violence and gore on TV, in movies and remain relatively unaffected.

And this “unaffectedness” is because death has become a commodity. A thing. Something we can look at. Removed from person, and removed from emotion.

Death as a commodity is, in many ways, like pornography. It’s become something that we can safely substitute for the real thing. It’s all the visuals without the love, the trust, the grief and the person. Just as pornography is the commodity of sex without love, so our present grasp of death (via TV, video games, etc.) is death without person and without grief.

And yet, while violence is all throughout our TV shows and video games, we are really uneasy when we talk about the real thing. It’s all the gore without the grief, which – like sexual pornography – doesn’t always prepare us for the reality of death and the grief that comes with us.

Death porn can make us insensitive to a co-worker who is “grieving longer than he/she should”. “Shouldn’t Pat be over that death by now?” If all we know is death porn, then the answer is “Yes. Pat should be over that death by now.” With death, there are no “one night stands” but death porn makes us think there is.

When death becomes pornified, it becomes something that we should “shield the children from.” So, like we often do when talking about sex around our children, we bath our language with euphemisms.

Grandpa has been:

“Called home”

“Gone to a better place”

“Gone to glory”

And when someone dies in the family we make sure that our children don’t have to see it. We “block that channel.” We are so used to the scary fantasy of death that we don’t realize how much beauty, love and life is in real dying, real death and real grief.

Finally, we learn to do death in private. Sure, we might have a funeral (although funerals are become less and less of a social occasion), but we don’t want others to see us grieve. When a friend asks, “How are you?” we won’t say how much grief hurts, we won’t let our friend see our emotions; instead, we’ll say, “I’m fine.” And so we’ve denied it. We’re ashamed of it. We feel guilty. “I just don’t want to be a burden to them.” As though death and grief is something that should be kept away, hidden and private.

But death isn’t pornography. Death isn’t dirty. Death isn’t something we should deny. Like sex, in the context of love, death is full of beauty, love and life. What good sex is to a good relationship, so the good death is to a community. Death provides that experience where the community – despite our differences — can come together as one.

The pornification of death robs us all. It hurts us, hurts our relationships and hurts our community.