The Sad, Sweet Story of the Man Who Lived In a Mausoleum

Every cemetery has its stories, as does every soul at rest within its grounds. Cemeteries serve as sacred places where visitors can remember those souls and those stories in peace and solitude. Sometimes, cemeteries are the only place mourners feel they can truly connect with the ones they’ve lost.

That was the case with Jonathan Reed of Brooklyn, New York. Just before his wife of 35 years, Mary Gould Reed, died after a lingering illness, Jonathan made Mary a promise.

“I told her I would never leave her; that I would be her one and only, forever,” he recalled 10 years later as he stood outside Mary’s tomb in Brooklyn’s Evergreens Cemetery. “She was beautiful in all things. Lovely, loving, and lovable. She was my inspiration and guide. I was successful in business and in many other things, and it was all due to her. So why shouldn’t I remain devoted to her?”

Jonathan was sharing these memories with a reporter from The Buffalo News in 1903 for a story that would take up nearly the entire front page of the paper. The heartbreaking headline read, “Man has lived ten years in wife’s tomb and vows to never leave her side.”

At the time, Jonathan had spent every day, from nearly daylight to dark, for the previous eight years in the tomb in front of which he granted the reporter an interview. For the first two years following Mary’s death, she was buried in a tomb owned by her father, who grew tired of Jonathan’s daily visits and forbade him to come by. After his father-in-law’s death, Jonathan paid $3,000 to build a new tomb that would hold his deceased love and, one day, his own body. He was only trying to keep his promise.

“Because there had never been any confidences withheld from each other, I told her of my plans to do just what I am doing now; that I would build a beautiful tomb and sit by her side every day. Whether she knows or not that I am keeping my vigil I cannot say, but I believe she does.”

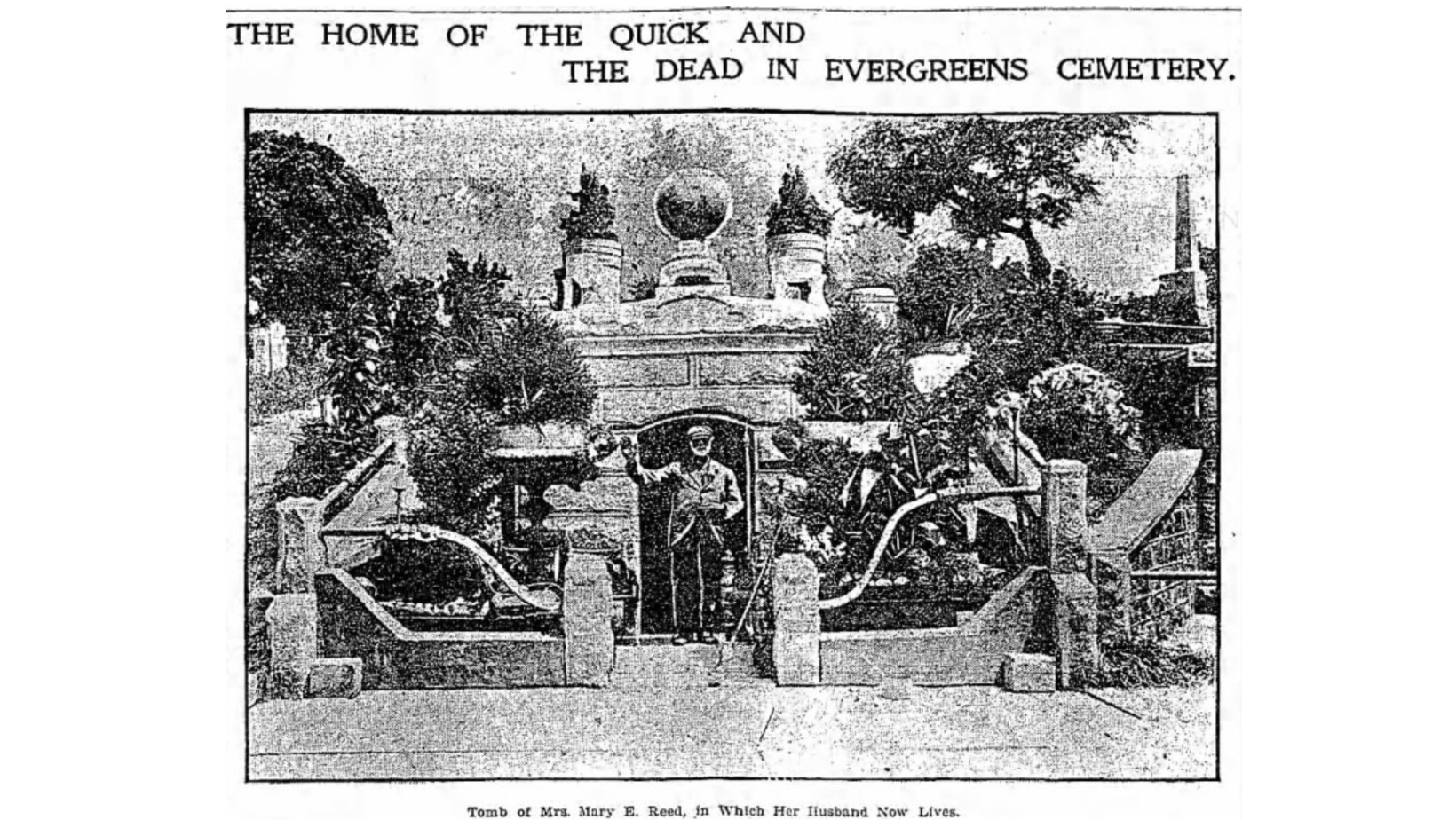

The tomb was built into a hill that rolled down to a lovely lake in a section of the Evergreens called Whispering Grove. It was simply built of granite blocks, with a huge globe atop the roof, urns at the front, and the names “Jonathan and Mary E. Reed” inscribed over the door.

At the time of the interview with The Buffalo News — one of dozens Jonathan had given over the years due to his peculiar vigil — a low stone-and-iron gate created an enclosed courtyard at the entrance to the tomb. Jonathan had filled it with grasses, shrubs, and plenty of flowers — all the varieties Mary had tended to at the home they shared in life.

“A landscape gardener might not quite approve the intermixing of sunflowers, phlox, asters, hens-and-chickens, and such homely old garden flowers with ivy and myrtle for cemetery decoration,” the News reporter wrote, “but to Mr. Reed they are more beautiful than choicer blossoms would be, for the reason that they were the kind of the home where he lived so many years with the one he loved.”

Within the courtyard also stood several iron benches to accommodate visitors. People came from far and wide to meet the man who lived in the tomb. In September 1895, just two weeks after Jonathan moved his wife into her forever home, The New York Tribune wrote that “thousands of people flocked to the cemetery yesterday to catch a glimpse of the retired merchant.”

The curiosity of the community wasn’t just due to the fact that Jonathan was a regular visitor, standing at the cemetery gate when it opened at 7am and feeling it close behind him at 7pm Many people stopped by because he had outfitted the tomb with the comforts of home — and many of these comforts came from his very own home.

In the aforementioned courtyard, white knobs removed from his old home’s doors decorated a flower box, and pans and kettles from Mary’s kitchen held well-tended plants.

The cavernous vault provided plenty of room for more of the couple’s precious belongings. After entering the space through the massive iron-barred door, visitors walked into a room that was described by the News as “8 or 10 feet square.” At the back of this room was an eight-foot passageway with niches carved out of either side.

Mary’s dressing table and mirror stood at the end of the passageway, decorated with “various small articles of feminine use.” Jonathan used the accompanying chair to sit beside his wife, who rested in the niche on the right in a metal casket, the open lid revealing a panel of glass through which Jonathan could gaze upon her every day.

When the casket was closed, it was covered with a “piece of cheap Japanese matting, gaudily painted with flowers, which evidently once served for a window shade,” according to the News. Heavy draperies that once surrounded the windows of the Reed home now framed the matching niches on both sides of the passageway.

When interviewed in 1903, Jonathan was using the niche on the left to store an “extraordinary collection of objects” from clothing to vases to pieces of his wife’s unfinished knitting. These items lay piled on top of his own expensive and empty casket.

Along the walls of the passageway and front room hung framed photographs and portraits, along with shelves filled with overflowing baskets of more knitting and knick-knacks, eating utensils, and one of Mary’s handbags.

Other items were suspended from the ceiling with twine, including a deck of cards Mary once used to play whist and a brass bird cage in which is perched the stuffed remains of Mary’s pet parrot. Tables were stacked with books, cushions, needlework, and a pail of water with a tin dipper. Above the door hung a cardboard sign that read “God Bless Our Home.”

In addition to the implements Jonathan used to tend to his exterior courtyard, he also kept a broom and mop to tidy up his daytime living space, even though he seldom received visitors other than reporters within those quarters.

According to several of the stories these reporters filed, the cemetery’s caretakers grew tired of the constant stream of lookey-loos, the number of which Jonathan estimated to be 7,000 during the first year of his residence, including 70 priests, 22 people from England, six from Germany, and six from Jerusalem. In 1896, officials forbade the opening of the tomb except to relatives and in special cases, by permit only, and of course, to Jonathan.

“The crowds that flocked to the tomb became a nuisance,” the cemetery superintendent told The Sun in May 1896, “and a little over a month ago I had a talk with Reed about the matter. I regarded his custom of keeping ‘open house’ at the tomb for the delectation of people who had no business there as a desecration. When the people learn that this practice has been stopped I think the attendance will dwindle away.”

Sometimes, though, visitors would spot Jonathan outside the tomb, sitting on a bench in his courtyard, looking down the hill to the lake, enjoying the singing birds and admiring his flowers.

Despite his self-imposed solitude, Jonathan repeatedly told reporters he wasn’t one bit lonely, and he wasn’t in mourning.

“People come and ask me,” he told The Sun, “why I don’t go to Coney Island or Bergen Beach instead of staying around this tomb all day long. I reply that I don’t see why I should go to Coney Island to see dancers and people standing on their head. I had rather be here beside my wife. I don’t come here to put on a long face and go around weeping. I come here where everything is beautiful.”

Some ascribed Jonathan’s behavior to a psychological issue, while others believed he was practicing supernatural practices and trying to summon his wife’s spirit to speak with him. However, Jonathan himself dispelled the spiritual rumors, saying that he could go without hearing Mary’s voice as he was still able to see her face. As for the former accusation, reporters repeatedly found his disposition pleasant and decidedly sane.

“There is considerable misapprehension regarding the motives that induced him to take up his present residence, wrote a reporter for The Voice of the People in 1900. “The casual observer would suppose that he is possessed of a peculiar state of mind bordering on insanity, though one has only to engage in conversation with him for a few moments, when the fact of his sanity will be established in the mind of the visitor. Mr. Reed possesses a sense of humor that will save a man from becoming despondent. He laughs like a man who lives amid scenes of mirth, instead of one who spends most of his time in and about a tomb.”

Although the 1903 anniversary of Jonathan’s 10-year vigil warranted front page coverage, the passing of time and the cemetery’s ban on visitors led to less and less attention being paid to the 70-plus-year-old widower — the cemetery “hermit” as he had begun to be called. Thus, on the 23rd day of March in 1905, when a cemetery worker went to investigate the open door to the Reeds’ tomb, he didn’t even know the identity of the man lying prostrate on the marble floor, barely breathing. Jonathan Reed wasn’t identified until after the police, and then a doctor, arrived and pronounced that he had been stricken down by a “stroke of apoplexy.”

Over the next two months, Jonathan would be moved to the residence of his niece — as his only living family members were a handful of nieces and nephews — and suffer two more debilitating strokes. The last one paralyzed him, and he was transferred to a sanitarium, where in September 1905, Jonathan Reed passed away. His death was covered in a few papers, along with short recollections of his peculiar cemetery home where he spent most of his last 12 years of life.

On September 12, 1905, a small crowd gathered outside the tomb of Jonathan and Mary Reed as a Manhattan pastor preached a brief funeral sermon. Jonathan’s body was transferred from a wooden coffin to the elaborate metal casket that had awaited his arrival for so long. Then, cemetery authorities locked the tomb, securing one key for themselves and throwing the only other copy inside the tomb through the iron door.

Today, the facade of the Reeds’ tomb in Evergreens Cemetery in Brooklyn looks much different now, as the stone-and-iron gate has been removed, and the carefully tended garden with its flower boxes and ornaments is long gone. Nevertheless, the site still draws visitors who learn about this story of enduring love and want to pay homage to the couple, who are now truly together forever.

“I loved her in life,” Jonathan told the Times Union in 1897, “and I love her still in death. When we meet in heaven, if there be a heaven, what a joyous meeting ours will be! But if we should never meet again I want to be close beside her to the last. This life is altogether made up of sentiment. What would it be without sentiment and love?”