All the Living and the Dead: Is it Dark or is it Illuminating?

“We are surrounded by death. It is our news, our novels, our video games–it is in our superhero comics, where it can be revered on a monthly whim. It is in our nursery rhymes, our museums, our movies about beautiful murdered women….The real and the imaginary intermingle, become background noise. Death is everywhere, but it’s veiled, or it’s fiction. Just like in video games, the bodies disappear.” Hayley Campbell, page 5

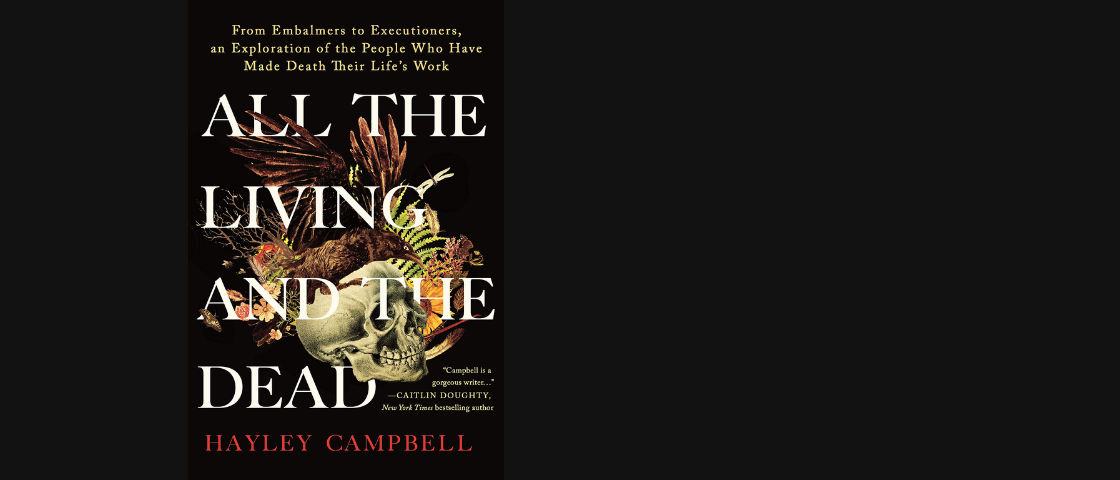

When I first saw an advertisement for Hayley Campbell’s All the Living and the Dead in mid-August on a New York Times Books (@nytbooks) Instagram post, I thought, “Wow, what a perfect opportunity to explore the culmination of my job as a deathcare media professional and a former literature student!” But I really had no clue what I was getting myself into. Before I cracked open the creative non-fiction book, I wondered subconsciously who else would be reading about such a niche subject. All the Living and the Dead follows Campbell’s investigation of all the people who have based their careers on death.

But this is not just a book full of interviews with funeral directors, undertakers, and gravediggers. It’s a transcontinental chase for answers to a childhood fascination with all things death consisting of conversations with death mask sculptors, crime scene cleaners, Anatomical Pathology Technologists (APT), and many, many more. She covers not only the natural death so commonly found in funeral homes but also murders and accidents that don’t shy away from her lifelong question of who “cleans up the mess.” There is no hiding from the realities of death in this book. A regular reader may wince or be fascinated; for those who are surrounded by the concept of death every day, it’s a refreshing point of view in a narrative format.

The light

This book is as much a self-reflection as it is an investigational piece. Campbell starts by telling us that she doesn’t have a memory of when she first understood that all living things die. I don’t either and I can relate to her in that sense. She is spurred by childhood loss, an almost universal experience, to do her research, and by the fact alone, many readers might be drawn to her work because they have the same questions floating in the back of their heads.

Along with the 10+ interviews, I enjoyed the mini-history lessons threaded within the chapters and how deathcare differs in other parts of the world compared to the U.S. (Campbell is an Australian based in London—explaining the British spelling and the sometimes puzzling punctuation.) For example, in the U.K., a funeral director needs no license to handle the dead.

While reading one might feel a horrified fascination. On her journey, Campbell visits a mortuary, giving a very vivid description of helping prepare a body for a funeral sans embalming, with facts of decompositional science thrown in. She visits the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota and the reader finally learns how medical cadavers are used. The anatomist who shows her around shares that he tries to instill in his medical students’ minds that they are working with a real person who donated their body out of generosity and should be respected. For example, he leaves nail polish and tattoos on the bodies as a physical reminder. She also visits the Cryonics Institute where one can elect to freeze their body in liquid nitrogen with the hope of restoration with technology in the future. Death doesn’t have to be the end of hope. The light of this book is that there is so much respect for the dead everywhere Campbell visits.

The dark

There were definitely a few chapters that were hard to get through. When seeing bodies in an embalming or medical setting Campbell feels what she calls an “emotional silence” (p. 41). At the Mayo Clinic, she realized that she had the stomach to see a certain thing, in this case, the bodies (whole and dissected) because she wanted to be there—just like the anatomist and the bodies themselves. And this “silence” alone might be chilling to readers because they might not be able to process these situations from Campbell’s journalistic standpoint.

If you’re an idealist, brace yourself for Ch 6: Dining with the Executioner because you’ll be faced with the inhumanity of U.S. capital punishment (a necessary realization in my opinion). I felt myself recoil more in this chapter than in any other. But I still encourage you to read it.

Some of the hardest chapters to get through featured interviewees who met bodies right after they died. An APT tasked with finding out the cause of death and hiding it again for families awaiting a funeral (Ch 8: Love and Terror). A bereavement midwife who delivers only babies that are dead or soon-to-be-dead (Ch 9: Tough Mother). Campbell herself had trouble seeing tiny stillborns at a ward funded by the U.K.’s Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Charity. Every reader has the right to pause or skip these chapters. Just remember that the people Campbell writes about deserve to be seen.

The first part of the book feels abject, a literary/cultural theory concept Campbell later talks about. Bodies, bodies, bodies. Midway through feels sad. When the purest thing in the world is taken away, the death of babies, we feel sadness within ourselves. There really is no disclaimer for the potentially triggering chapters, so read with care.

My recommendation

I think All the Living and the Dead is a fascinating book and it kept me engaged the entire 237 pages—but you have to ask yourself what is inspiring you to read it. While I truly enjoyed it, I certainly would not recommend this book to someone who recently lost a loved one (unless they express interest). Nor someone who is grieving and has not yet made it to a place of acceptance (as no grief journey is linear). This book deals with death just as it is, not the way a recent loss is padded with life celebration services, kind words, and gentle treading around the bereaved.

Campbell has such a unique way of describing the settings she finds herself in, her own perception of the people she meets, and the bodies she witnesses. On more than one occasion I let out an impulsive laugh. For example, when she imagines a theoretical body is found in their house she comments that “the food in the that outlasted its owner” (p. 5). I let out a singular, somewhat-shocked laugh and wondered, can I laugh at that? And this is just one of many occurrences. She is a very blunt and honest writer and one can’t help but admire her for that.

Who would have thought Campbell could have written this book or convinced people to read it, but she did. For readers outside of deathcare, she’s trying to reveal the death hidden from society. If it’s your prerogative to keep it hidden, by all means, find a book that’s right for you. But for those of us who deal with death more frequently, this is a unique experience to see it from someone else’s eyes who, in turn, is looking through a magnifying glass.

In the words of Ron Troyer, the embalmer Campbell talks to in Chapter 7, it is sometimes a negative shock to see a body but most times it helps families in their grief journey. But he has learned in his trade that “people are much stronger and much more capable of doing things than we give them credit for” (p. 129). And your strength might outweigh the uncomfortable truths that make up this book.

This is a book whose author is trying to solve the mystery of what happens to a body after death and who cares for it—a mystery that society has created for itself. It is reality. This book is an answer to a question. And so to read it, you must first ask yourself what question are you trying to answer?