Abraham Lincoln: The President Who Made Embalming Great Again

President Abraham Lincoln packed a lot of accomplishments into his four short years in office. He ended the Civil War, issued the Emancipation Proclamation, established a national banking system, and created the Department of Agriculture. But did you know that he’s also responsible for popularizing embalming in the United States?

Your mortuary science curriculum probably included a course on the history of the funeral service in America. Before the 1860s, you’ll recall, preparation of body, viewing, and burial were all managed by the deceased’s family members – usually by women, and usually in the home. But the time from death to interment could be days or weeks while families waited for loved ones to arrive by stage or train. In warmer climates, especially, the effects of decomposition inevitably would begin to take their toll.

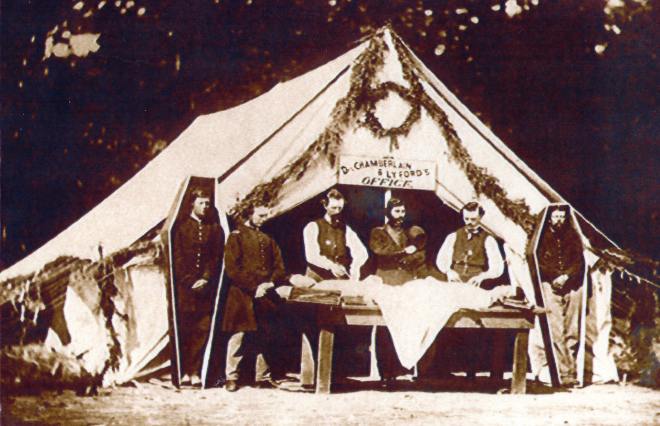

Battlefield embalming

This is exactly what happened on the Civil War battlefields. At the beginning of the war, hundreds of bodies could lie where they fell until they could be interred in impromptu cemeteries, rolled into mass graves, or personally retrieved by family members or caring strangers. Many families, especially Northerners who felt burial in Southern soil was an atrocity) requested that the body of their loved one be transported home, but even tightly sealed, “airtight” metal caskets didn’t slow the rate of decay during the journey.

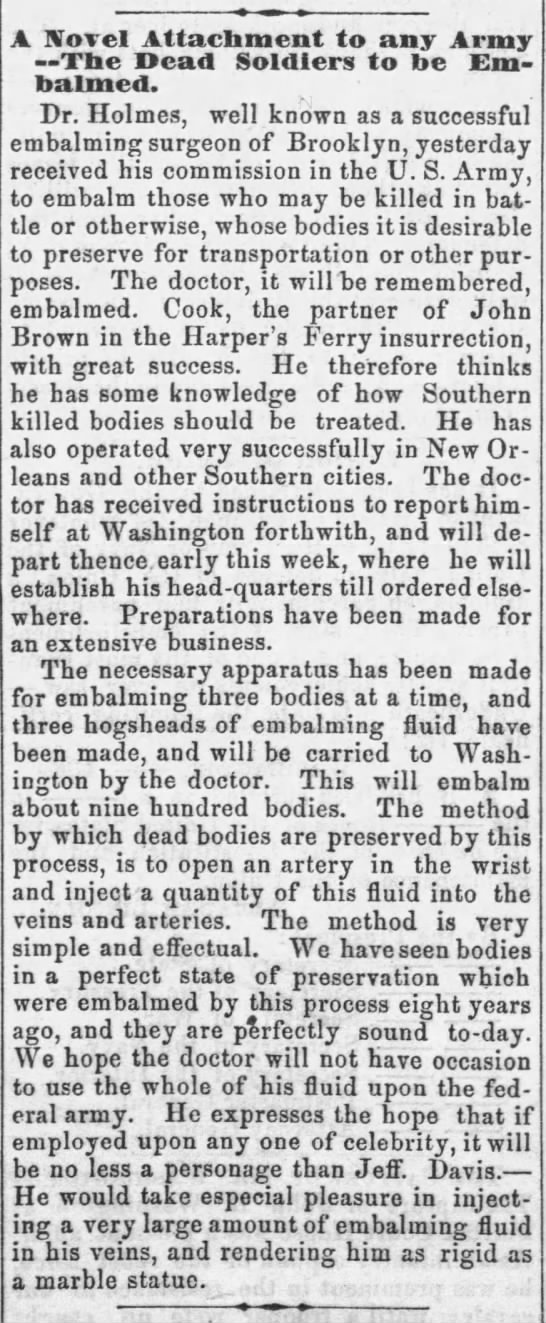

Around this same time Thomas Holmes, a physician in Brooklyn, New York, was researching phrenology, which involved the measurement of cranium shape and size in relation to mental traits. While studying the heads of Egyptian mummies, Holmes realized that this ancient civilization had found a solution for preserving human bodies without dangerous chemicals, and invented his own concoction of preservation fluids.

Holmes famously tested his technique on the body of Union Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, who was killed on May 24, 1861 while removing a Confederate flag from a hotel in Virginia. Ellsworth, the first Civil War officer to die in the line of duty, was also a close friend of Abraham Lincoln. The President was impressed by the appearance of Ellsworth’s body, and quickly commissioned Holmes to embalm U. S. Army soldiers.

When Lincoln’s 11-year-old son Willie died of typhoid fever on February 20, 1862, Lincoln asked Drs. Charles Brown and Harry Cattell to embalm the boy. Willie was interred in a family friend’s vault in Washington so that his father could visit frequently, sometimes even opening the casket to view his son.

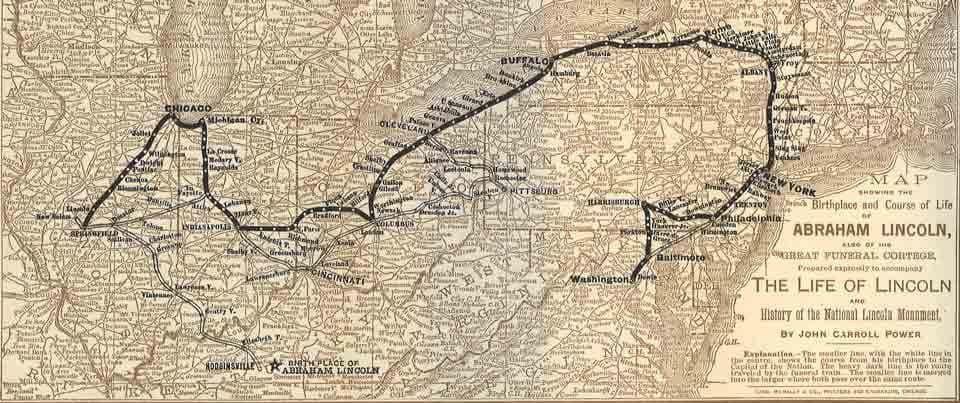

Lincoln funeral train

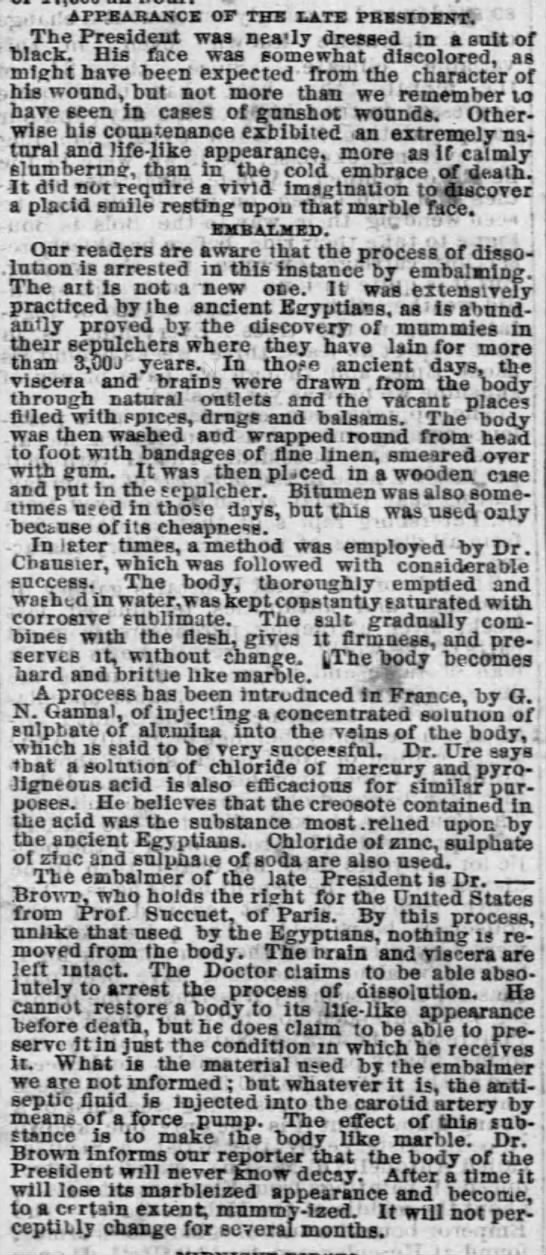

Brown and Cattell were called upon three years later to embalm the President after his assassination and death on April 14, 1865. Using a French embalming mixture described by the Chicago Tribune on May 2, 1865 as “a concentrated solution of sulphate alumina,” the doctors were able to “make the body like marble” so that it would “not perceptibly change for several months” and would “never know decay.”

Preservation was imperative for the the body’s 1654-mile,13-day journey by train to Springfield, Illinois, Lincoln’s hometown. After lying in state for three days in the rotunda of the Capitol in Washington, the funeral train carrying Lincoln departed on April 21, 1865. Accompanying Lincoln to Springfield for burial were the remains of his son Willie, who was to be entombed alongside his father.

The train traveled through 180 cities and seven states, making stops to allow mourners to pay their respects to the slain president. During these events, Lincoln’s coffin was taken off the train and moved in procession to a public building for viewing. People were amazed at the lifelike appearance of Lincoln’s corpse. Even on May 2, nearly three weeks after his death, Lincoln’s “face was somewhat discolored,” a characteristic attributed to the gunshot wound, but otherwise his “countenance exhibited an extremely natural and life-like appearance, more as if calmly slumbering, than in the cold embrace of death,” according to the Chicago Tribune reporter.

Dr. Thomas Holmes is said to have performed over 4000 embalmings during the Civil War, which was a fraction of the total 40,000 soldiers reported to have undergone “field” embalmings. Following Holmes’ 1861 success, so many amateur embalmers preyed upon families hoping to preserve the remains of their loved ones that the government had to issue General Order 39 to restrict the embalming of military personnel during wartime to only licensed professionals. This licensing process eventually led these individuals to set up storefront displays of embalmed bodies to showcase their work, which, in turn, gave way to the establishment of professional funeral services and parlors.

While Dr. Holmes deserves some of the credit for changing the funeral practice it was ultimately the prominent display of Abraham Lincoln’s well-preserved corpse that led to the mainstream embalming practices we know today.