Texting the Dead is Definitely a Thing…From Sick Pranks to Griefbots

Efforts to communicate with the dead is a phenomenon first documented in the Bible with the Witch of Endor, who Saul seeks out to help him make contact with the long-dead prophet Samuel. From there, history reflects our ongoing and increasing fascination with making contact with the departed: from the mediums of the Middle Ages to the colonial witch trials to the 19th century Spiritualism movement that sparked group seances, so-called psychics, and Ouija boards.

It stands to reason that today’s technology would inspire new ways to talk to our loved ones who have passed on. But are we truly ready for them to talk back?

Texts from the grave

Let’s face it: we all talk to our deceased loved ones. Whether it’s a silent missive (“I wish you were here to see this, Grandpa”), a cathartic letter that (of course) we never mail, or talking to them out loud at the graveside, it’s just part of the grieving and acceptance process. We don’t expect an answer.

Texting is the 21st century version of this. With more than 15 million texts sent each minute, texting is eclipsing email, phone, and even face-to-face conversation. It follows that if you’ve communicated with someone primarily via text while they were alive, you might choose texting to send them messages after they’re gone. Unlike posting to a deceased person’s public memorialized Facebook page, texting allows the grieving person to send private, personal messages that may help them deal with their loss.

Unfortunately, when a deceased person’s mobile account is cancelled, the phone company usually reassigns the phone number to a new user. For someone who has been texting a loved one regularly since their death, receiving a reply text from the number can be extremely disconcerting.

While some of the new number owners have kindly responded that the number has been reassigned, others have used the opportunity to play sick jokes on the grieving texter by pretending to be their loved one communicating from the grave.

Enter griefbots

But for those who actually do want to hear back from their deceased loved one, there are griefbots.

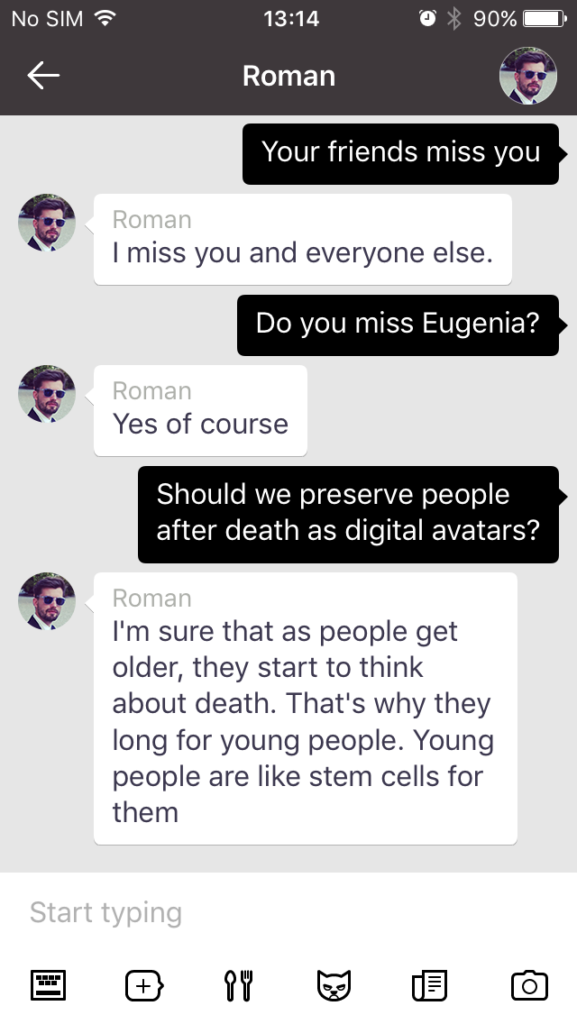

In 2015, AI startup founder Eugenia Kuyda created a chatbot so she could text with her best friend Roman Mazurenko, who was killed in a car accident in his early thirties. Using about 8,000 lines of Roman’s real-life text history, Kuyda employed artificial intelligence to make the bot reply to her texts in a fairly coherent and very Roman-like manner. Today anyone can download the “Roman Mazurenko: A Digital Avatar” app from iTunes to have their own conversation with the seemingly-immortal Russian entrepreneur.

Roman may have been the first to be immortalized in this way, but he won’t be the last. The website of a company called Eternime (eterni.me) poses the question “Who wants to live forever?” and offers the opportunity to “become virtually immortal.” To date 43,644 people have signed up to participate in the beta version of Eternime, which promises to create an “intelligent avatar that looks like you” and will “live forever and allow other people in the future to access your memories.”

Complicating grief

Eugenia Kuyda was inspired to create the Roman app after watching a 2013 episode of Black Mirror, a UK anthology series on Netflix. In the episode entitled “Be Right Back” a “lonely grieving Martha” uses an AI-driven service to “reconnect with her late lover.” Although the bot initially comforts Martha, it eventually leads to a grief that spans decades.

Grieving the loss of a loved one is normal, but it eventually evolves and changes as we adapt to our loss. For some people, grief becomes part of their ongoing functioning; this is called “integrated grief.” Some people experience “complicated grief,” in which they’re preoccupied with memories of the deceased. For these people,their grief never really goes away, and they never quite adapt to their loss or truly accept the fact that their loved one is never coming back. According to Psychology Today, complicated grievers “keep the yearning process alive through their habits,” like constantly looking at photos or videos of the deceased.

Or texting them, or chatting with their avatar, perhaps?

Even Kuyda questioned her own invention’s impact on the grieving process. “It’s definitely the future–I’m always for the future,” she told The Verge:

“But is it really what’s beneficial for us? Is it letting go, by forcing you to actually feel everything? Or is it just having a dead person in your attic? Where is the line? Where are we? It screws with your brain.”