Who Should Have Called Foul When Cryonics Lab Took a Swing at Ted Williams’ Frozen Head?

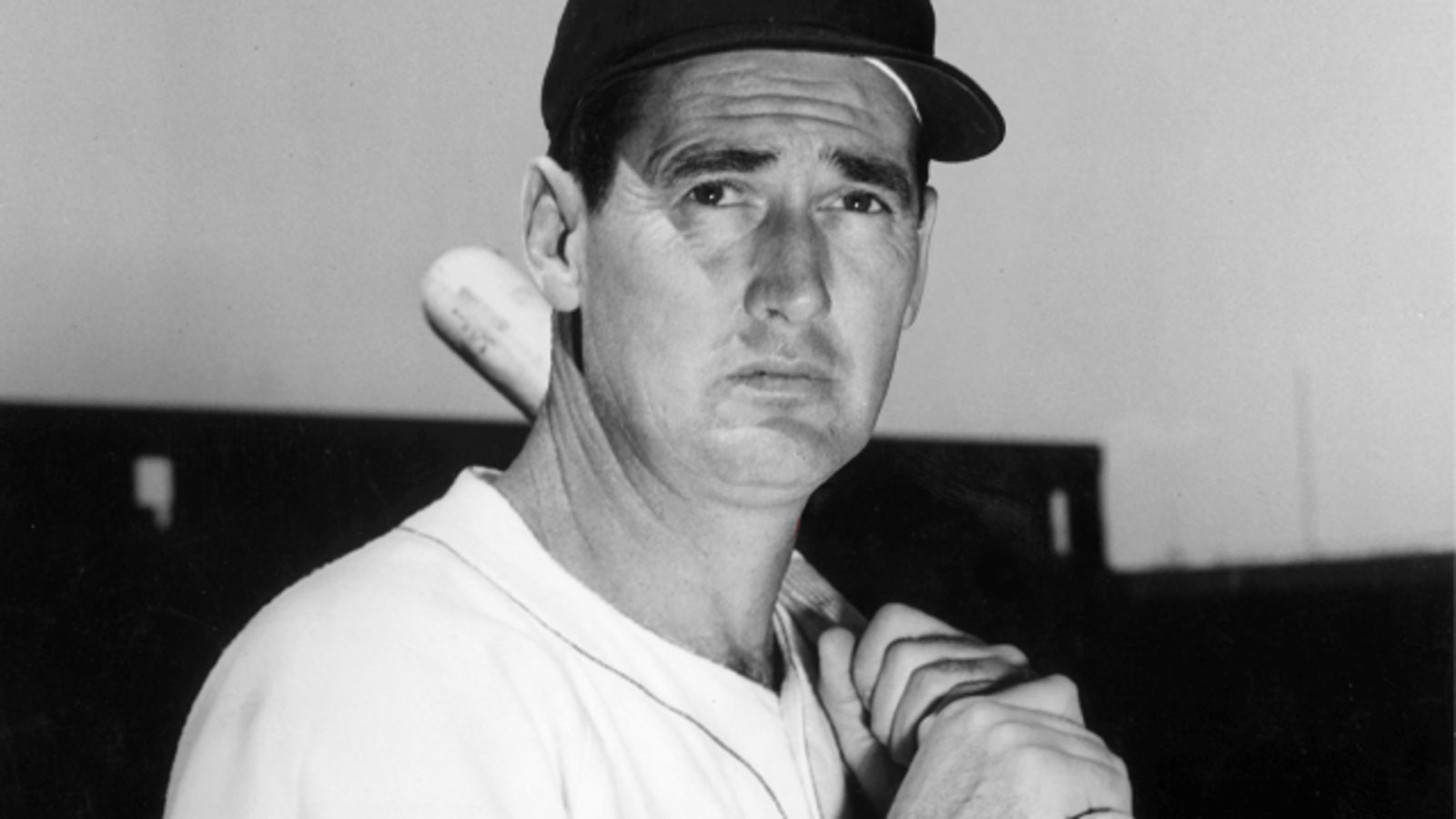

Ted Williams was a baseball legend. During his 21-year career with the Boston Red Sox, he won six batting titles, led the American League in home runs and RBIs four times, and was the last Major League player ever to hold a .400 batting average, ending his 1941 season with a .406. Even at 39, he was hitting .388. His performance led to his 1966 induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Today, though, when someone mentions the name “Ted Williams,” it isn’t his phenomenal performance on the field that first comes to mind. Unfortunately, it’s his ongoing status as a decapitated, mutilated, cryonically-frozen body that’s now permanently attached to his memory.

Final wishes?

When a famous person passes away, we expect a brief flutter of activity in the media — maybe a 60-second spot with a highlight reel and an “In Memoriam” screen. And the more distant their fame from current events, the less screen time they garner. But from the moment Williams died on July 5, 2002 at age 83, he’s been making news.

First it was the decision of two of his three children to honor William’s wishes to have his body cryonically frozen (the third sibling fought to have her father cremated, as he had originally requested). Within months the news broke that Williams’ remains had been decapitated by surgeons and stored separately from his body in the Scottsdale, Arizona Alcor cryonics facility. To an audience still puzzling over the science of cryonics and Williams’ hopes to one day be revived, this was an atrocity. As a footnote, it was also reported that several samples of Williams’ DNA were missing.

But the worst was yet to come. Fast forward seven years to 2009, when a book by a former employee of Alcor hit the shelves containing explosive allegations of Alcor’s abusive treatment of Williams’ frozen head. Author Larry Johnson wrote that an empty tuna can was used as a pedestal to support the slugger’s head while experiments (which subsequently cracked his frozen brain) were conducted. When the tuna can became stuck to the head, an Alcor employee allegedly tried to dislodge it by swinging at it with a monkey wrench, in the process missing the can and connecting with Williams’ head instead. Johnson wrote that the impact sprayed “bits of frozen head” around the room.

Patient rights

Alcor denied Johnson’s claims, promised legal action, and the spotlight on Williams and Alcor faded once again. But in 2016, the subject raised its ugly head once again when a terminally ill 14-year-old girl in the United Kingdom announced her intentions to be be cryonically preserved. It seems that any story about cryonics inevitably mentions Williams; as arguably the most famous individual to be frozen in liquid nitrogen, his name is now inextricably linked to the industry.

The 2016 cryonics controversy called for regulation and argued for patient rights — but not the kind that would have prevented or punished the alleged mistreatment at the Alcor lab. Instead, the discussion involved determining exactly who decides if a body will be frozen — the decedent, next of kin, or the state.

For other methods of disposition, the rules are clear, as are the regulations surrounding the ethical and lawful treatment of human remains. In 2004, Arizona Senator Bill Stumps introduced a bill calling to remove authority of cryonics in Arizona from cryonic scientists and facilities like Alcor and transfer authority to the Arizona Board of Funeral Directors and Embalmers.

“Funeral home scandal”

Alcor, the only cryonics facility in Arizona and one of only three in the United States, responded by publishing an open letter from Dr. Brian Wowk, a prominent organ preservation researcher. In increasingly-passionate language, Wowk first argues that the bill falsely compares cryonics to embalming, and therefore is “comparable to the Funeral Board assuming authority over the job of a brain surgeon.”

Wowk then addresses the “allegations of wrongdoing” regarding the separation of Ted Williams’ head from his body (the monkey-wrench-to-tuna-can story was at the time five years away). Calling the stories a “witch hunt,” Wowk wrote:

“Consider if a journalist did this expose of the funeral industry: ‘Funeral Home Scandal: Bodies injected with poison, organs mutilated, remains stuffed into wood boxes and covered with dirt!’ It’s all true, right? Of course, if a disgruntled apprentice embalmer went to a sports magazine describing in graphic detail the use of a trocar during embalming of a sports celebrity, or the physical effects of cremation, he would be escorted out of the building by security.”

Of course, patient rights and who regulates the cyronics industry are just two of a multitude of issues being debated. Discussions continue about how or if life insurance policies should be paid when the insured could potentially be brought back to life, whether or not revival of the body is even feasible, and even if attorneys should continue to offer “revival trusts” for when the cryonically preserved person comes back.