Inside the Machine That Will Turn Your Corpse Into Compost

Article originally published by: Wired

WHEN YOU DIE, do you want to be buried or cremated? If the architect Katrina Spade gets her Urban Death Project to work, you might have a third option: compost.

If Spade’s first recomposition center opens in Seattle in 2023 as planned, it’ll be an airy, spiritual place where people can carry their loved ones’ corpses to a final rest—and put those corpses’ decomposition to an eco-minded use. She describes the facility as part funeral home, part place of memorial, and part public park. “I think there’s value in creating places where we’re thinking about death and its role in our lives, and the fact that it’s coming for all of us,” Spade says.

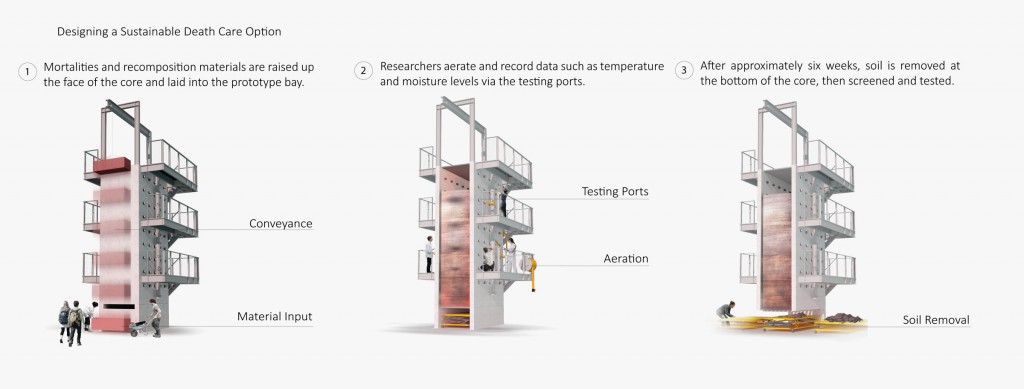

The trick is getting the decomposition right. Spade is working with soil scientists to perfect the process, and designing the building around the concrete core that’ll make it work. Imagine a three-story rectangular silo filled with wood chips, with a room on top. During memorial services, mourners carry the shrouded body up a ramp that winds around the core to this room. Here, the family members lower the body onto a bed of wood chips inside an open door in the floor. That door is the top of a 6-foot-by-10-foot concrete bay that adjoins multiple other bays, like a grid of elevator shafts. Mourners cover the body with additional wood chips and close the door.

Over the next four to six weeks, the body will move slowly downward as it decomposes, and as the material below it condenses and is removed. That timeline is based on the livestock mortality composting experience of Lynne Carpenter-Boggs, a soil scientist at Washington State University. When animals used in the university’s agriculture programs die, the school composts them in specially designed piles, where a large carcass can decompose—even the bones start breaking down—in one to two months. But no one has tried composting, with livestock carcasses or human bodies, in a vertical system like Spade’s.

Next year, Spade and Carpenter-Boggs will do just that on the WSU campus. Using hog carcasses and, later, donated human bodies, they’ll find out how long it takes a body to sink from the top to the bottom. In Spade’s working design, each bay is 24 feet tall and accommodates six bodies at a time, with 3-foot layers of wood chips between them. Fans aerate the decomposing material to accelerate decay, pulling air from ports in the side of the bay, directing it through the core’s contents, and expelling it via a filtered vent. The same ports permit the addition of water and sugar solutions to stimulate microbial activity.

Spade and Carpenter-Boggs estimate that by the time the material reaches the bottom of the bay, it will be a coarse loam no longer recognizable as human remains. After that, in a room at the bottom of the core, staff (some very, very special folks) finish and cure the compost. Magnets screen out material like metal dental fillings, and employees process the compost into a finer, soil-like material. At least, that’s the idea.