What’s That? You Want to be Buried How?

Recently my father called me to make the following announcement:

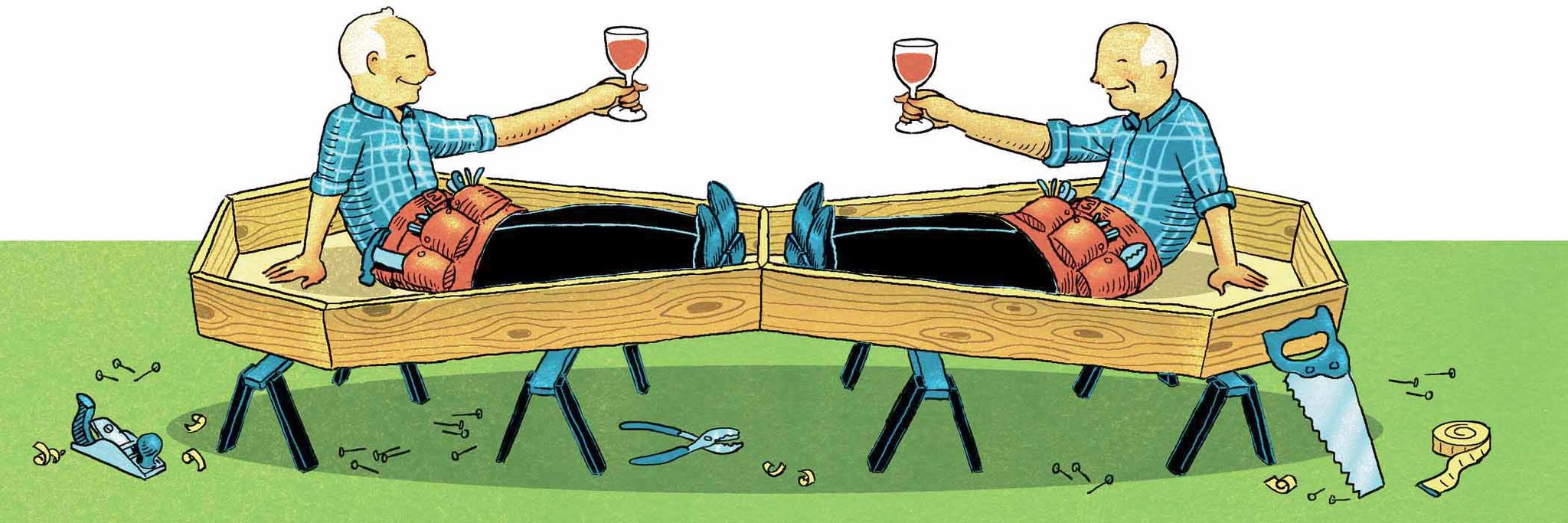

“I’ve decided that I’m going to be buried toe-to-toe with Lester Davis — and I’m immensely happy about it,” he said.

Lester Davis is my father’s best friend.

“But you mustn’t say anything to Zohra about this,” my father added.

Zohra is his wife.

My father is in perfect health, so the phone call prompted no immediate alarm, but it did make me think that my father can’t be the only one with surprising plans for his ideal forever.

The example set by Jeremy Bentham, the 18th-century English philosopher, might be considered truly avant-garde. Mr. Bentham asked that his head be embalmed and fixed on top of his skeleton, which was to be dressed in his own black suit and placed in a glass case, “in the attitude in which I am sitting when engaged in thought,” as he put it.

One can see him like this still, in a central hallway of University College London (though the embalming of his head was not successful, and had to be replaced by wax). Legend has it that for years after his death, Mr. Bentham continued to attend faculty meetings, where he was counted as “present, but not voting.”

The philosopher aside, “the idea of using your corpse to reflect your individuality is relatively recent,” writes Bess Lovejoy, the author of “Rest in Pieces: The Curious Fates of Famous Corpses.” One can make a final bid for immortality, or opt for an altogether differently flavored legacy: the witty, the impish or the out-and-out profane.

Justin Frank, a psychoanalyst and author of “Obama on the Couch,” among other books, had to think deeply about how to honor his own father’s request. His father, also named Justin Frank, had been a physician in Beverly Hills, Calif., and a lifelong iconoclast.

The elder Dr. Frank had repeatedly told his children that when he died, he wished to have a certain profanity, one not printable here, inscribed on his gravestone.

“He had a real hatred of the hypocrisy of ceremonies,” explained the younger Dr. Frank, who, with his sister, eventually came up with a solution to satisfy their father’s request. They sent instructions to the Hollywood Cemetery to have an acrostic inscribed on the tombstone, one that accomplished the task. Dr. Frank remembers getting a phone call from the startled stonecutter: “Are you aware of what this spells?”

(Dr. Frank is currently entertaining his own burial fantasies. He has not worked out the details, but said he felt strongly that “we shouldn’t take up extra space after we die.” Because of his deep connection to dogs, it is Dr. Frank’s wish to be “turned into dog treats,” he said.)

Franklin D. Roosevelt left a careful list of specifications for his own burial, including the instruction that “the casket be of absolute simplicity, dark wood, that the body be not embalmed or hermetically sealed.” To this last detail Gore Vidal is rumored to have quipped: “Being Franklin, he wanted to get back into circulation as soon as possible.”

Yet the conspicuous trend, many funeral directors say, is toward cremation, which has spawned an entirely new set of choices.

For instance, you can, if you like, wear your loved one on your ring finger in the form of a purple crystal, courtesy of such websites ascremationsolutions.com (select “cremation jewelry”).

Hunter S. Thompson had his ashes dyed green, silver, blue and red and shot out of a cannon over his property in Colorado.

Timothy Leary, famous for his pioneering studies of LSD, had his ashes shot into space, where they orbited until 2002.

Upon his death five years ago, the artist Stephen Irwin left a request in his will: that his ashes be turned into graphite pencils.

“My friend wants her ashes spread inside the Frick Collection,” Irene Deitch said. “She’s there all the time.”

Ms. Deitch is a New York psychotherapist and certified thanatologist; the term refers to the study of death and dying. She has long taken note of the exquisite care and effort devoted to final appearances.

She recalls attending the funeral of a patient’s mother. When she arrived, she heard her patient saying furiously to her sister: “I can’t believe you’d let Mom be buried in that,” and dispatching her sister to Nordstorm to purchase a suit, moments before the service was to begin.

There was also the woman, a friend of Ms. Deitch, who, given a fatal diagnosis, got a face lift, to look her best in her open coffin.

Ms. Deitch said she always found it striking to hear mourners complaining about the appearance of the corpse.

“They say, ‘That doesn’t look a thing like Dad,’ ” she said. “But what did they really expect the cosmetologist to do, restore life?”

What might fuel these detailed fantasies, even among those who would not admit that they believe in an afterlife? To find out, I consulted Caitlin Doughty, a funeral director and writer. Ms. Doughty, 30, is best known for her popular podcast “Ask a Mortician,” as well as her recent book “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes: And Other Lessons From the Crematory.”

She lives in Los Angeles in an apartment befitting her macabre credentials: Her walls display artifacts of all kinds, including the contents of a tuberculosis doctor’s medical bag from the 1920s. A model skull keeps her company at her writing desk.

Ms. Doughty, who studied medieval history at the University of Chicago, entered what might be called “the death industry” at 23, working in a San Francisco crematory, driven by the urge to understand what goes on behind the scenes. Immediately, she was struck by the schism, or as she says, “the black curtain” drawn between those whose job it is to tend to the dead, and those whose isn’t. “Do people really know what is our relationship with death right now?” she wondered.

Ms. Doughty said she believed that we have drifted too far from death in our daily lives, losing touch with this fundamental part of “the fabric of experience.” She referred me to her touchstone text, the 1973 classic “Denial of Death,” by Ernest Becker.

In it, Mr. Becker argued that most if not all of what we devote our lives to — our ambitions, achievements, our parties, our children — can be understood as an attempt to fight an underlying awareness of our own mortality. Perhaps it is not such a stretch to imagine that we continue to struggle against death even in death itself.

Last month, I was on hand when a manila envelope arrived for my father containing photographs of his burial plot, now picked out and paid for. My father inspected them with an air of great satisfaction, happy to imagine himself there next to his best friend forever. I do hope they have a good time.

[H/T: NY Times]