“Embalming Surprises: Tales of the Preparation Room”

Article Provided By Jeff Seiple, Georgia Campus–Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine

I recently took my car to a local mechanic for a routine check-up. As most people do, I dropped the car off and asked the mechanic to call me at work once he was finished. Well, one hour later, he called and reported that I needed new rotors and brake pads. I paused for a minute and pondered what he told me. At that point, I responded and said, “Go ahead and replace the front rotors.” He said he would; however, he went on to say—“There is more!” By this time, my body started to instantly tense up and a wave of emotion started to overtake me. Obviously, I was not expecting any further complications nor expense. As most of you know, there is always added expense. Moreover, I said in a stern voice, “What else have you found wrong with my car?” He went on to say that my water pump was leaking and by the way I might as well replace the serpentine belt. He said that he could replace everything for $1,900.00!

By this time, a 1970’s theme song from the sitcom Hee Haw started playing over and over in my mind. You might remember it. It went something like—“Gloom, despair, and agony on me. Deep dark depression, excessive misery……” Tell me you remember this. Anyhow, I think you get my point.

I remember saying to the mechanic, “I haven’t noticed any problems.” Also, I said that the car performed well and that I had not noticed any problems while driving it. His response was, “Sometimes life throws you a surprise, but we can handle it.”

If you are still reading this article, have you ever been dealt a major surprise in life? Or, let me re-phrase my question: “Has anyone ever encountered a surprise while embalming a body in your preparation room?” Is your answer an undisputed “yes!” for both questions? If you answered yes, then you are not alone! In fact, you will probably agree with some of the preparation room surprises that I have encountered during my twenty-eight years of experience within the preparation room. So, let’s get to what this article is really about.

Embalming surprises come in different ways. Each case that we embalm presents its own level of difficulty. For the seasoned embalmer, navigating around a difficult embalming is fairly easy. I say fairly easy because most experienced embalmers have worked on a number of challenging cases and have, therefore, applied various successful techniques that have been taught to them throughout their time in the funeral profession. Is it fair to say that, today, new embalmers as well as seasoned ones are still amazed and surprised during certain embalming operations? I feel certain the answer is yes!

Consider just a few of the cases we deal with today and one would probably conclude that each of the following has the potential to afford a “newbie” or seasoned embalmer a challenge and/or higher level of difficulty or, if you like, call it an occasional “Surprise.”

1. Post-Mortem Autopsy ( including tongue extraction–Glossectomy)

2. Edematous Cases

3. Long-Term Preservation and/or Delayed Embalming

First, let us discuss the full-posted autopsy case that we prepare. Imagine a situation where you start preparing this case based upon the techniques taught to you in the preparation room. All of a sudden, for example, as you disinfect the oral cavity with an appropriate orifice disinfectant cleaner of your choice, you notice that the subject to be embalmed has had his/her tongue removed. Could this interfere with embalming distribution and diffusion in the subject’s head? You “betcha” it can! Surprise! When conversing with different people around the country, many of them tell me that their medical examiner’s offices are removing the tongue as a routine practice during the post-mortem autopsy. It is examined in an effort to identify residue that might possibly contribute to and/or justify the true cause and manner of death. Removing the tongue is, seen by some M.E.’s as part of the total or complete autopsy procedure.

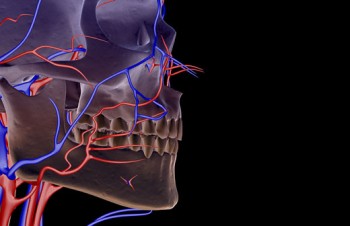

During normal embalming protocol, embalmers inject the head of the subject after they have injected the lower and upper extremities of the full-posted case. When injecting upward, via the left and right common carotids, you may notice that your fluid may not properly distribute into the face of the subject that you are embalming. For some embalmers, they will elect to inject that side of the face needing embalming fluid, via the appropriate facial artery. The place of incision for locating the facial arteries is made on the posterior one-third of the inferior margin of the mandible, just anterior to the angle of the jaw. This technique can be beneficial in delivering preservative fluid to one or both sides of the face. (See figure 1.)

While discussing surprises, one must admit that the injection of the lower extremities also leads to some surprising problems from time to time. For example, many times medical examiner’s assistants or pathologist’s assistants will draw blood just inferior to the iliac region on one or both legs. In their effort to obtain a sample of blood, from the femoral vein, they sometimes puncture and/or compromise the external iliac artery or arteries. As you know, most embalmers inject the lower extremities of the full-posted case via the left and right external iliac arteries. The result is that an extravascular leak will occur and that the fluid distribution will cease to continue throughout the rest of the leg or legs. In other words, little if no embalming fluid distribution will occur through the femoral arteries and eventually down to the feet. (See figure 2.)

Today’s practicing embalmers are taught in mortuary colleges and funeral homes to externally inspect the body from head to toe before they start the operation. It is during this initial inspection that a prudent embalmer will identify the punctures made in the iliac area. In short, be ready to raise and inject the femoral artery or arteries, just below the puncture(s), when one clearly observes the punctures on the superficial skin area of the iliac region.

There is an old expression that says, “Chance favors the prepared mind.” In other words, embalmers should anticipate that they will have to raise the femoral or femoral arteries for the purpose of continuing their fluid distribution down the left and/or right legs. This should not be a surprise given that you have identified where the M.E.’s office has drawn blood. Be prepared!

Second, edematous or dropsical cases can present their own set of problems. As most of us know, edematous fluids within a body can predispose that case to early decomposition. Generally, these types of cases require a hypertonic or strong primary dilution. It is worth mentioning that many embalmers, including myself, will add some type of edema eliminating co-injecting chemical to their primary dilution. This primary dilution additive has the ability to crenate and/or shrink cells within tissues that are literally saturated with water. Moreover, the dehydrating ability of these chemicals can be very effective in reducing swollen areas due to water retention, and in many cases, help an embalmer to achieve a more overall successful appearance within the embalmed body.

Also, I have learned that gravity and elevation, along with a proper primary dilution strength, make a great partnership. The correct elevation of extremities generally aids embalmers when they are trying to remove edematous fluids. First of all, an embalmer should not assume that a general primary dilution injection from the right common carotid will correctly treat an edematous limb. Case analysis dictates that we inject a stronger primary dilution in closer proximity to the edematous extremity. Injecting edematous legs via the femoral arteries is one of the first techniques that I was taught during my internship. This process not only involves injecting the edematous limb(s), but also demands that an embalmer slightly elevate the legs of the deceased, after the injection, and place cotton wicks or thin rolls of cotton within the femoral incisions. The edematous fluids gravitate toward the femoral incisions and the fluids are attracted through the cotton wicks and consequently drain in the corrugated area of the embalming table.

Once the edematous fluids have had time to drain, then the embalmer may tie off the femoral arteries and properly close the incision(s). It is wise to place the lower limb(s) in plastics such as stockings and or capri pants. As you know, edematous fluids can possibly continue to manifest and possibly contribute to further leaks from the legs. However, you knew this—right? The moral of the story is to use plastics as a final barrier. You do not need any surprises once the body has been dressed and/or casketed.

Third, every embalmer tries to achieve the best form of disinfection, restoration, and preservation that he/she can. We are all taught, in mortuary college, that all three components add up to insure a quality embalming operation. However, are there times where we know that a body will be embalmed and we will be charged with the responsibility to hold it, in our funeral home, for an extended period of time? The answer is yes! Does this mean that we should try to over-embalm this particular case? Of course not!

Also, what if we have to delay embalming for some reason? What factors might affect the embalming operation once we have clearance to proceed with the operation? Is it possible that a body that has been refrigerated for an extended time period might manifest swelling and/or distention during arterial injection? Certainly, it is possible. Surprise, the capillaries of a refrigerated body can sometimes be damaged by cool and/or extended cold refrigeration. However, it should be no surprise that an embalmer must consider letting this case thaw properly and also consider decreasing their rate of flow when they start the arterial embalming process.

Additionally, there will be certain intrinsic and extrinsic factors that we have to take into account as we consider arterially embalming a body whereby injection was delayed and also when we have confirmed that we will have to hold on to this body for an extended time period. Because the possibility of longer time periods before embalming and longer holding periods exist, we should specifically consider the following factors:

1) How long the body will be held

2) Where will we keep the body: In a refrigeration unit or at room temperature

3) Is the body severely dehydrated and/or emaciated

4) Is the body already showing signs of decomposition –i.e., Desquamation (skin slip)

5) What is the Cause and Manner of Death

6) Does edema exist within the body

From the previous list, just consider dehydration, alone, and take into account how dehydration can affect an arterial embalming operation that has been delayed and also where the funeral home has confirmed that it will hold the body for an extended amount of time. The question might be, “Can we balance potential dehydration factors along with achieving long-term preservation?” I believe we can. Likewise, should we modify the strength of our primary dilutions to meet the long-term preservation and anti-dehydrating requirements of this body? The answer is yes. Today’s professional embalmer must be thoroughly educated about how to correctly mix the right primary dilution for a case that will be held for a considerable amount of time while taking into consideration measures to avoid or manage surface and/or deep tissue dehydration.

Here’s a case in point—I was called upon 3 years ago to embalm a seven year old child by a local medical examiner’s office. The assistant pathologist told me that he did not know how long he would retain the body within his morgue. At this point, I thought there must be more to this case than he is telling me. After further conversation, he filled me in with as many details as he could. As you have already guessed, the plot thickens! The events surrounding the death of this child were broadcast throughout the local media outlets!

To make a long story short, the body was fully autopsied and remained in the morgue for approximately three weeks after the autopsy. During the fourth week, the assistant pathologist contacted me and requested that I embalm the body. The body arrived at my lab and I quickly realized that I had better prepare the correct primary dilution. First of all, I filled my embalming machine with ½ gallon of water. I then chose to mix 3 ounces of a well-known 28 index arterial fluid as well as 3 ounces of a humectant based 25 index arterial chemical to my solvent.

The embalming went beautifully and I was very pleased. The tissue was pliable, but fixated. I felt the addition of the humectant based arterial fluid would help to retain moisture and not create any future dehydration within this precious little body. Two weeks later I was embalming at the local medical examiner’s office. I asked if I could check on our little body to confirm that my primary dilution was correct. The body was in great shape. No signs of dehydration were present. The body’s lips had not parted, nor were there dehydration wrinkles on the head, hands, or feet.

A month and a half later, I found out that the child was claimed and a viewing and funeral were conducted in the Atlanta area. The embalmed body of this child had remained in the refrigeration unit of the morgue for that duration. At that point in time, one of my students approached me, one day, in the hall, where I taught, and congratulated me for the great embalming that I had performed on this child. I had to think a minute and then realized whom he was talking about; after all, the embalming of this child had taken place a month and a half earlier. I quickly reviewed my notes and the case report that I filled out after the embalming. I then called the funeral home and talked to the director who handled the service. Surprise, I now had positive verbal confirmation, from not only my student, but also from the funeral home that handled the service!

I had achieved credible, in my opinion, proper long-term preservation even though the time period of embalming was 3-4 weeks after death.

In conclusion, I have learned that each aforementioned case presents its own set of embalming challenges. Likewise, I have learned that each case presents a new experience! Speaking of experience. One of my former teachers always pontificated: “Experience is what you get when you didn’t get what you want.” Ponder that pithy comment, for a moment, and I will bet that you agree with it! Yes, it is true that sometimes in life, just like in the preparation room, we are all dealt surprises. Some are good and not so good. However, the difference between the good and the bad lies in how we react and learn from the experience. Yes, experience is truly the teacher, but knowing how to apply one’s experience is probably just as important.

Bibliography

Anatomy for Funeral Service, 1st Edition, Professional Training Schools, Inc.

4722 Bronze Way, Dallas, Texas 75236. Copyright @ 2000.

Embalming History, Theory, and Practice, Fourth Edition, Robert Meyer, McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division. Copyright @ 2006.

The Principles and Practices of Embalming, Fifth Edition, Copyright @ 1989, Professional Training Schools, Inc. and Robertine Frederick. Fifth edition reprinted 1990, 1991, 1992.

Superstock.com, Anatomical Images, Superstock, 7660 Centurion Parkway, Jacksonville, Florida 32256

About the Author

Jeff Seiple is the Anatomical Coordinator for the Georgia Campus of the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine located in Suwanee, Georgia. He was previously associated with Gupton-Jones College of Funeral Service where he worked for over 25 years. In his previous role, at the College, he taught the Embalming Curriculum and managed the College’s Embalming Clinical Program. Over the years he has authored various articles for industry trade magazines dealing with embalming. He has been a sought after seminar speaker through the years for the: National Funeral Directors & Morticians Association, The South Carolina Funeral Directors Association, The Georgia Funeral Directors Association, The Independent Funeral Directors of Florida, The Order of the Golden Rule, and The New Jersey State Funeral Directors Association.

In addition, he has served as an embalmer and presenter for the annual Georgia Academy of Graduate Embalmer’s Clinic for years. Jeff is a former member of the Region IV. Disaster Mortuary Operational Response Team (DMORT). He has co-authored the book entitled: “Alpha to Omega in the Preparation Room.” Jeff is a licensed Funeral Director and Embalmer in Georgia and Florida. He holds an M.B.A. from Brenau University. During his career, he has especially enjoyed teaching many funeral service students to whom he refers to as friends! Jeff lives in Marietta, GA with his wife—Julie. He can be reached at the Georgia Campus of the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine by email at: jeffreyse@pcom.edu or seiplejeff@hotmail.com