Should the Excess Heat from Cremation Be Recycled?

Recycling the excess heat from cremation might not sound like the most obvious way to honour your loved ones, but for the environmentally aware, it could be a more efficient way to create energy.

Dr John Troyer, deputy director of Bath University’s Centre for Death and Society (CDAS), is currently grappling with some of the moral issues – such as whether the process is respectful to the dead – surrounding the process, which is known as heat capture.

He has become a familiar presence at funeral services held at the city’s Haycombe Crematorium. A sombre job, perhaps, yet crucial to his one-year research project, which is funded by the South West Regional Development Agency and European Regional Development Fund.

Haycombe was among the first crematoria in the country to install expensive equipment that prevents mercury emissions from the cremation process escaping into the atmosphere. Heat capture could, in time, be a possibility there, but it’s sensitive territory and Troyer is at pains to tread carefully, steering clear, for instance, of canvassing the bereaved for their views. “My father was a funeral director,” he says. “I’m very conscious of not being cavalier – projects can be torpedoed if you don’t keep in mind exactly what you are dealing with.”

Besides exploring moral questions around heat capture, he is also learning about developments in technology. As other crematoria install new equipment to comply with rules on reducing mercury emissions, some are making profitable use of excess heat that otherwise would be wasted.

But Troyer’s work is concerned as much with the ethics of heat capture as with the process. “This research isn’t about trying to design a system per se, but asking how you design for the future and create facilities that are used more efficiently – current crematoria designs are late 19th century,” he says. “It’s about the relationship between death, the body and technology.”

The onus is on UK crematoria to halve mercury emissions, which come mainly from tooth fillings, by 2012 and eliminate them altogether by 2020. Many will need to install new equipment. Those that have already invested in heat-capture technology usually divert the excess heat to other crematorium buildings.

Some crematoria in Sweden and Denmark have gone further, selling surplus heat for use in houses. Many see this as entirely sensible, avoiding the need for crematoria to have expensive and energy-hungry cooling towers. But others wonder if it breaches an ethical code drawn up the International Cremation Federation, a body set up in 1937 to promote and provide information on cremation practice. This states that “the products or residue of a cremation shall not be used for any commercial purpose”.

The issue is so sensitive that the Danish Council of Ethics, a group including scientists, clergy and philosophers that advises parliament, was summoned to give its opinion. After much deliberation, it found no ethical reason to oppose recycling heat despite the ICF code. Several crematoria now export energy to local companies.

The UK has a long way to go in comparison, although a new system at Redditch, Worcestershire, will pipe water to heat a swimming pool and save local council taxpayers around £14,500 a year. Councillors sought to forestall an outcry by consulting the public beforehand and 80% to 90% of responses were in favour, it says. Nevertheless, there were instances of what Troyer describes as “moral outrage”. At the time, a spokesman for the public sector union Unison described the scheme as “sick and an insult to local residents”.

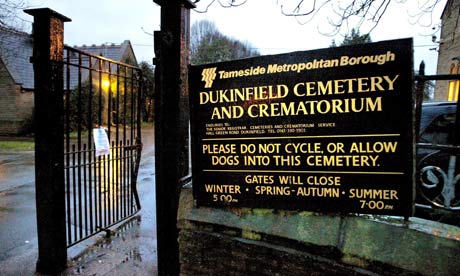

Troyer believes such knee-jerk reactions are triggered by ignorance about what is involved. After cremation, water is used to cool gases in the crematorium chimney. Mercury is filtered out, and water heated by the cooling process then piped away. Surplus heat harnessed in this fashion is now being used in chapels and offices at Dukinfield, Cheshire, Warwickshire and Sandwell Valley, West Midlands.

“Most of it comes from the gas used to get the fire burning – a negligible amount from the bodies themselves,” says Troyer. “But you are entering an area of public concern. There are questions that need to be sorted out and taken up with local and national authorities. You have to get policy-makers thinking about it. That isn’t a simple thing to do.”

For those UK crematoria that hold lots of daily services, the amount of excess heat generated could open up the possibility of selling energy to the National Grid.

The economic argument for heat capture would appear compelling in countries such as Japan, where over 95% of the dead are cremated (in Britain the figure is 72%). But Troyer thinks it unlikely every culture would take the same liberal view as Denmark over selling energy to a network. Here, the Federation of Cremation and Burial Authorities (FCBA) is quite relaxed about this use of technology. “There’s been a fair bit of hype – talk of family members heating the swimming pool,” says its secretary, Richard Powell. “But we don’t see any ethical issues.”

Tim Morris, chief executive of the Institute of Cemetery and Crematorium Management, supports “any innovative approach with environmental benefits”. He says plans to install heat-capture equipment at a crematorium in Cardiff provoked no hostility after staff took to the streets and explained how it works.

Troyer says he is not trying to court controversy. Rather he is using Haycombe as a base to look more broadly at possible future designs, while studying all aspects of the ethical debate. “Some grieving families like the idea of their loved ones ‘giving back something’,” he says. “I see that becoming predominant, and this research as an opportunity to do something innovative and respectful to the funeral mourning process.”