Unclaimed Dead Await Final Resting Spot at LA Cemetery

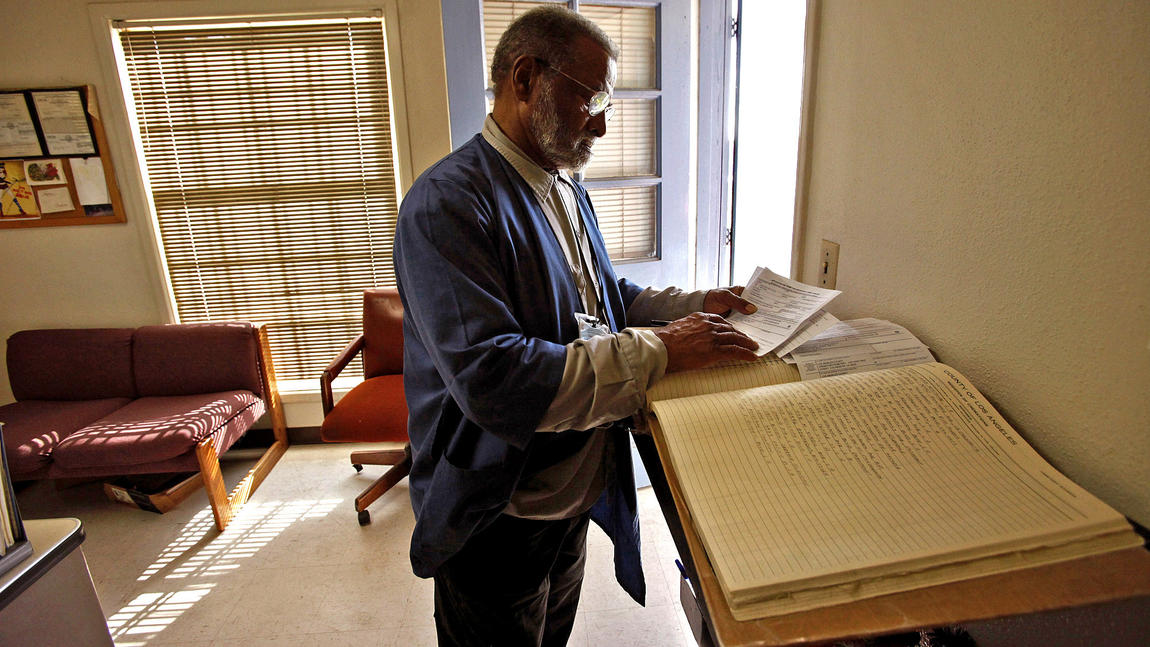

Clear shipping tape covers the oversized ledger, holding together the corners. Its 1,000 pages threaten to overwhelm the three large flat-head screws that clamp the spine. Inside, names and dates fill row after row in near-perfect script.

This is the book of the unclaimed dead.

They die in hospitals in Torrance, in nursing homes in Long Beach, on the street in Los Angeles.

About six bodies arrive each day at L.A. County’s cemetery in Boyle Heights. There, Albert Gaskin gives each body a round metal tag with a cremation number.

As he has done for more than three decades, Gaskin records the tag’s number and the dates of the cremation and the cremation permit in the ledger. The name comes next. Then date of birth. And sex. Race. Date of death.

36164.

JULY 13, 2011.

JULY 9, 2011.

WHEELOCK, JOHN R.

11-19-46.

M.

CAUC.

6-9-2011.

On a second page, there’s a location of death or coroner case number. And there’s a space for a signature — that means the body has been claimed.

On Wheelock’s entry, and most of the others, the space is empty.

Wheelock is on Page 289 of the book, which is kept in a safe in a chapel-like room at the county crematory with other books listing the unclaimed dead buried at the cemetery. The smallest book, a “Register of Burials,” dates from Jan. 1, 1896, to April 30, 1902. Recent books contain about a decade’s worth of names.

The first cremation in the latest book was recorded Oct. 29, 2005. Those cremated today are added near the back of the ledger. Two hundred sixty-one pages in, the names of those cremated in 2011 begin.

Ira Johnson, 77. Robert Lyman, 64. Luther McKenney, 74. Farther down the page are newborn twins Cassidy and Cameron Stansbary, who did not make it through their first day.

Until The Times digitized the handwritten record of the unclaimed dead of 2011 to create a searchable database, only those people whose cases were handled by the coroner — about a third — could be found online.

Officials from the Department of Public Health, which oversees the morgue and the Department of Decedent Affairs, said they are working to digitize many of their records.

But that won’t happen before December, when the ashes of more than 1,400 people cremated in 2011 will be buried in a mass grave in the Boyle Heights cemetery. It’s a lonely annual ritual attended mostly by local media and county employees.

For the unclaimed dead of 2011, time is running out.

Wheelock, who grew up in Southern California and graduated from San Bernardino Valley College with a degree in electronics, loved trains.

In the 1990s, he moved to Oregon and became a volunteer with Train Mountain in Chiloquin. The mountain stretches over 2,000 acres of pine forest with more than 36 miles of track, about 7 1/2 inches wide. It is one of the largest hobbyist railroads in the world.

Wheelock even owned a small, gas-powered locomotive — “big enough that you can actually ride on,” a fellow enthusiast said.

He was on the trip of his lifetime when he died at 10:30 a.m. on June 9, 2011.

He started at his home in Oregon and headed north to Seattle. From there he traveled east to Chicago. Then south to New Orleans. And west to Los Angeles.

When he found the right train and car at Union Station, he sat down. And then he grabbed his chest. Passengers in the train tried CPR. So did paramedics. But Wheelock died.

“It came at a horrible time,” said his son Aaron Wheelock, who couldn’t afford to come get his father’s ashes. The county wouldn’t ship them to his home in Idaho, he said.

If relatives can be found, they are notified by the morgue or the coroner that their loved one’s body is available for pickup by a mortuary. If a family can’t afford the mortuary fees, the county handles cremation.

The cost is typically $352 for a case handled by the coroner and $466 for others. Although that must be paid before the ashes can be taken, in some cases a family can ask a county supervisor to waive the fee.

Some families simply don’t want to pick up relatives, said Joyce Kato, an investigator at the Los Angeles County coroner’s office.

“We see that more and more every year,” she said. “They don’t even feel that they’re obligated to make arrangements for a long-lost sibling.”

In some cases, Kato said, family members are just interested in the death certificate, which gives them access to property, bank accounts and life insurance.

For others, no relatives can be found.

By late last month, of the 1,868 dead who ended up at the crematory in 2011, only 440 have been claimed.

Gaskin helps take care of the cremations, the ashes and the book of the unclaimed dead.

He starts as early as 4 some mornings. He picks up bodies from hospitals and takes them to the crematory on the hill in Boyle Heights.

Gaskin has been at the crematory since the late 1970s. He jokes that he’s 19. But really he doesn’t want to say how old he is. He’s past retirement age, but stays on because he enjoys the job and he feels like he’s taking care of people. In some cases, he’s the last one to care for the person before he or she is put into the ground.

“Maybe next year,” he said about retirement. (He chuckled because he says that every year.)

It doesn’t feel like work, he said. “I feel I’m doing a service and I enjoy it.”

He’ll probably opt for cremation after he dies, he said.

“I think I would want to be cremated the next day,” he said. “I just don’t want to be laying around with people moaning and worrying.”

And he’d like to be cremated by the county.

“It’s like if you go to a doctor, you’d want to go to a very good doctor because you know he’s going to take care of you,” he said.

But he added that he’d pay for the cremation and his son would claim his ashes.

In some pages of the book, the writing changes. Gaskin goes on vacation. Another worker records the names, adding flourishes on top of the C’s.

Cornelius, David. Born Nov. 4, 1940. Died Oct. 2, 2011.

The ashes to be buried this year belong to the old and the young. About two-thirds are men. More than half are white.

One hundred thirty-seven are babies. Some were stillborn; others lived for a short time. Instead of the brown plastic boxes that hold adults’ remains, babies’ ashes are stored in small paper bags, neatly folded like wallets and placed in metal drawers.

35335.

Cremation: FEB 16, 2011.

Permit: FEB 9, 2011.

GRANT, JACQUELINE.

B/G (baby girl).

Born: 2-6-2011.

Sex: F.

Race: A.A.

Died: 2-7-2011.

All the names of the unclaimed dead will eventually be online, said Andrew Veis, assistant press deputy for County Supervisor Don Knabe.

Knabe makes a point to attend the burial ceremony each December.

“The whole issue here,” he said, “is at least these folks are getting a respectful burial.”

When coroners are unable to find relatives they sometimes submit their request to unclaimedpersons.org, an online group of about 600 volunteers who scour public records for possible family.

Megan Smolenyak, an independent genealogist based in Haddonfield, N.J., founded the group, which draws up a report of likely relatives and submits that to the coroner or medical examiner who asked for help.

Smolenyak called unclaimed people a “quiet epidemic.”

“A lot of times you get to the heart of it and it’s some silly little feud,” she said. “You don’t have to mend bridges. Just keep in touch.”

When a body ends up at the crematory, Gaskin places a wide board about 5 feet long under it, then puts it onto a metal gurney.

He wheels it into the furnace room. The place is stale with dust. The room is noisy and hot from the furnaces.

Gaskin takes a long metal pole with a flat “T” top. He rests the top of the pole against the body’s shoulder and together with another man slides the body into the brick furnace. And the furnace’s door slides down.

The metal tag with the cremation number waits on the door as the body burns.

Gaskin turns around and heads out of the room to retrieve another body. There is always another body.

[H/T: LA Times]